How to build one of these for real:

Halo light bridge, from halo.wikia.com

Or indeed one of these:

From halo.wikia.com

I recently tweeted that I had an idea how to make the glowy bridges and shields we’ve seen routinely in sci-fi games from Half Life to Destiny, the bridges that seem to appear in a second or two from nothing across a divide, yet are strong enough to drive tanks over, and able to vanish as quickly and completely when they are switched off. I woke today realizing that with a bit of work, that it could be the basis of a general purpose material to make the tanks too, and buildings and construction platforms, bridges, roads and driverless pod systems, personal shields and city defense domes, force fields, drones, planes and gliders, space elevator bases, clothes, sports tracks, robotics, and of course assorted weapons and weapon systems. The material would only appear as needed and could be fully programmable. It could even be used to render buildings from VR to real life in seconds, enabling at least some holodeck functionality. All of this is feasible by 2050.

Since it would be as ethereal as those Halo structures, I first wanted to call the material ethereum, but that name was already taken (for a 2014 block-chain programming platform, which I note could be used to build the smart ANTS network management system that Chris Winter and I developed in BT in 1993), and this new material would be a programmable construction platform so the names would conflict, and etherium is too close. Ethium might work, but it would be based on graphene and carbon nanotubes, and I am quite into carbon so I chose carbethium.

Ages ago I blogged about plasma as a 21st Century building material. I’m still not certain this is feasible, but it may be, and it doesn’t matter for the purposes of this blog anyway.

Will plasma be the new glass?

Around then I also blogged how to make free-floating battle drones and more recently how to make a Star Wars light-saber.

Free-floating AI battle drone orbs (or making Glyph from Mass Effect)

How to make a Star Wars light saber

Carbethium would use some of the same principles but would add the enormous strength and high conductivity of graphene to provide the physical properties to make a proper construction material. The programmable matter bits and the instant build would use a combination of 3D interlocking plates, linear induction, and magnetic wells. A plane such as a light bridge or a light shield would extend from a node in caterpillar track form with plates added as needed until the structure is complete. By reversing the build process, it could withdraw into the node. Bridges that only exist when they are needed would be good fun and we could have them by 2050 as well as the light shields and the light swords, and light tanks.

The last bit worries me. The ethics of carbethium are the typical mixture of enormous potential good and huge potential for abuse to bring death and destruction that we’re learning to expect of the future.

If we can make free-floating battle drones, tanks, robots, planes and rail-gun plasma weapons all appear within seconds, if we can build military bases and erect shield domes around them within seconds, then warfare moves into a new realm. Those countries that develop this stuff first will have a huge advantage, with the ability to send autonomous robotic armies to defeat enemies with little or no risk to their own people. If developed by a James Bond super-villain on a hidden island, it would even be the sort of thing that would enable a serious bid to take over the world.

But in the words of Professor Emmett Brown, “well, I figured, what the hell?”. 2050 values are not 2016 values. Our value set is already on a random walk, disconnected from any anchor, its future direction indicated by a combination of current momentum and a chaos engine linking to random utterances of arbitrary celebrities on social media. 2050 morality on many issues will be the inverse of today’s, just as today’s is on many issues the inverse of the 1970s’. Whatever you do or however politically correct you might think you are today, you will be an outcast before you get old: https://timeguide.wordpress.com/2015/05/22/morality-inversion-you-will-be-an-outcast-before-youre-old/

We’re already fucked, carbethium just adds some style.

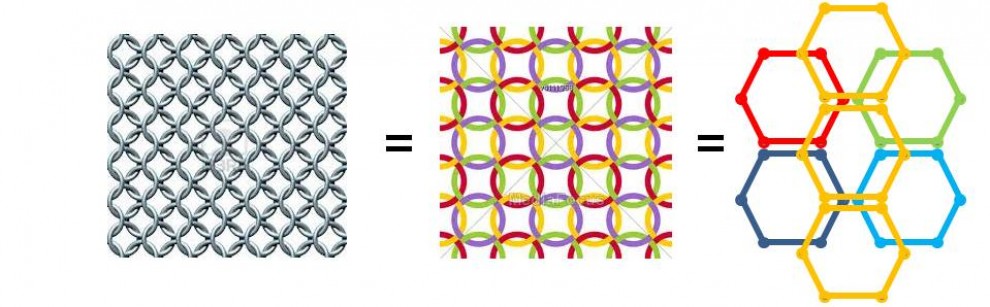

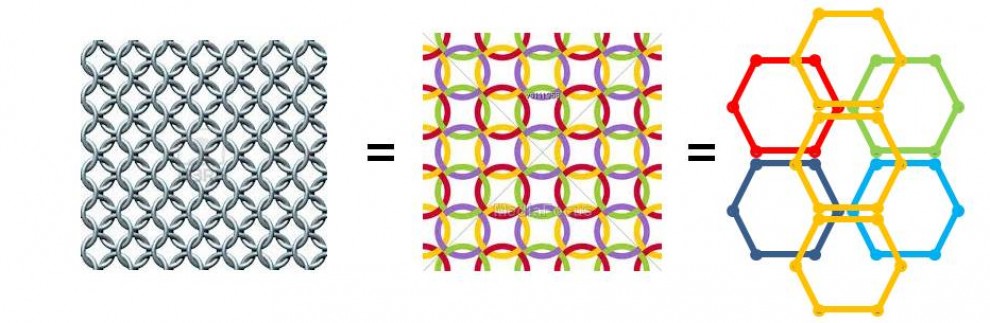

Graphene combines huge tensile strength with enormous electrical conductivity. A plate can be added to the edge of an existing plate and interlocked, I imagine in a hexagonal or triangular mesh. Plates can be designed in many diverse ways to interlock, so that rotating one engages with the next, and reversing the rotation unlocks them. Plates can be pushed to the forward edge by magnetic wells, using linear induction motors, using the graphene itself as the conductor to generate the magnetic field and the design of the structure of the graphene threads enabling the linear induction fields. That would likely require that the structure forms first out of graphene threads, then the gaps between filled by mesh, and plates added to that to make the structure finally solid. This would happen in thickness as well as width, to make a 3D structure, though a graphene bridge would only need to be dozens of atoms thick.

So a bridge made of graphene could start with a single thread, which could be shot across a gap at hundreds of meters per second. I explained how to make a Spiderman-style silk thrower to do just that in a previous blog:

How to make a Spiderman-style graphene silk thrower for emergency services

The mesh and 3D build would all follow from that. In theory that could all happen in seconds, the supply of plates and the available power being the primary limiting factors.

Similarly, a shield or indeed any kind of plate could be made by extending carbon mesh out from the edge or center and infilling. We see that kind of technique used often in sci-fi to generate armor, from lost in Space to Iron Man.

The key components in carbetheum are 3D interlocking plate design and magnetic field design for the linear induction motors. Interlocking via rotation is fairly easy in 2D, any spiral will work, and the 3rd dimension is open to any building block manufacturer. 3D interlocking structures are very diverse and often innovative, and some would be more suited to particular applications than others. As for linear induction motors, a circuit is needed to produce the travelling magnetic well, but that circuit is made of the actual construction material. The front edge link between two wires creates a forward-facing magnetic field to propel the next plates and convey enough intertia to them to enable kinetic interlocks.

So it is feasible, and only needs some engineering. The main barrier is price and material quality. Graphene is still expensive to make, as are carbon nanotubes, so we won’t see bridges made of them just yet. The material quality so far is fine for small scale devices, but not yet for major civil engineering.

However, the field is developing extremely quickly because big companies and investors can clearly see the megabucks at the end of the rainbow. We will have almost certainly have large quantity production of high quality graphene for civil engineering by 2050.

This field will be fun. Anyone who plays computer games is already familiar with the idea. Light bridges and shields, or light swords would appear much as in games, but the material would likely be graphene and nanotubes (or maybe the newfangled molybdenum equivalents). They would glow during construction with the plasma generated by the intense electric and magnetic fields, and the glow would be needed afterward to make these ultra-thin physical barriers clearly visible,but they might become highly transparent otherwise.

Assembling structures as they are needed and disassembling them just as easily will be very resource-friendly, though it is unlikely that carbon will be in short supply. We can just use some oil or coal to get more if needed, or process some CO2. The walls of a building could be grown from the ground up at hundreds of meters per second in theory, with floors growing almost as fast, though there should be little need to do so in practice, apart from pushing space vehicles up so high that they need little fuel to enter orbit. Nevertheless, growing a building and then even growing the internal structures and even furniture is feasible, all using glowy carbetheum. Electronic soft fabrics, cushions and hard surfaces and support structures are all possible by combining carbon nanotubes and graphene and using the reconfigurable matter properties carbethium convents. So are visual interfaces, electronic windows, electronic wallpaper, electronic carpet, computers, storage, heating, lighting, energy storage and even solar power panels. So is all the comms and IoT and all the smart embdedded control systems you could ever want. So you’d use a computer with VR interface to design whatever kind of building and interior furniture decor you want, and then when you hit the big red button, it would appear in front of your eyes from the carbethium blocks you had delivered. You could also build robots using the same self-assembly approach.

If these structures can assemble fast enough, and I think they could, then a new form of kinetic architecture would appear. This would use the momentum of the construction material to drive the front edges of the surfaces, kinetic assembly allowing otherwise impossible and elaborate arches to be made.

A city transport infrastructure could be built entirely out of carbethium. The linear induction mats could grow along a road, connecting quickly to make a whole city grid. Circuit design allows the infrastructure to steer driverless pods wherever they need to go, and they could also be assembled as required using carbethium. No parking or storage is needed, as the pod would just melt away onto the surface when it isn’t needed.

I could go to town on military and terrorist applications, but more interesting is the use of the defense domes. When I was a kid, I imagined having a house with a defense dome over it. Lots of sci-fi has them now too. Domes have a strong appeal, even though they could also be used as prisons of course. A supply of carbetheum on the city edges could be used to grow a strong dome in minutes or even seconds, and there is no practical limit to how strong it could be. Even if lasers were used to penetrate it, the holes could fill in in real time, replacing material as fast as it is evaporated away.

Anyway, lots of fun. Today’s civil engineering projects like HS2 look more and more primitive by the day, as we finally start to see the true potential of genuinely 21st century construction materials. 2050 is not too early to expect widespread use of carbetheum. It won’t be called that – whoever commercializes it first will name it, or Google or MIT will claim to have just invented it in a decade or so, so my own name for it will be lost to personal history. But remember, you saw it here first.