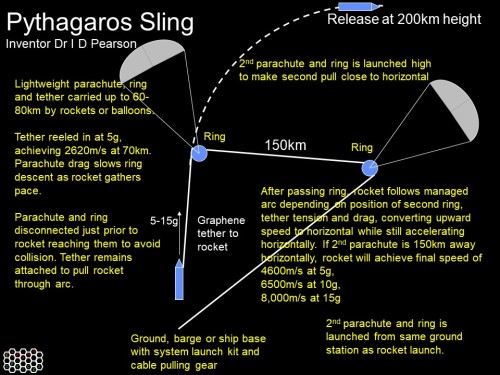

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing mission, I updated my Pythagoras Sling a bit. It now uses floating parachutes so no rockets or balloons are needed at all and the whole thing is now extremely simple.

Introducing the Pythagoras Sling –

A novel means of achieving space flight

Dr I Pearson & Prof Nick Colosimo

Executive Summary

A novel reusable means of accelerating a projectile to sub-orbital or orbital flight is proposed which we have called The Pythagoras Sling. It was invented by Dr Pearson and developed with the valuable assistance of Professor Colosimo. The principle is to use large parachutes as effective temporary anchors for hoops, through which tethers may be pulled that are attached to a projectile. This system is not feasible for useful sizes of projectiles with current materials, but will quickly become feasible with higher range of roles as materials specifications improve with graphene and carbon composite development. Eventually it will be capable of launching satellites into low Earth orbit, and greatly reduce rocket size and fuel needed for human space missions.

Specifications for acceleration rates, parachute size and initial parachute altitudes ensure that launch timescales can be short enough that parachute movement is acceptable, while specifications of the materials proposed ensure that the system is lightweight enough to be deployed effectively in the size and configuration required.

Major advantages include (eventually) greatly reduced need for rocket fuel for orbital flight of human cargo or potential total avoidance of fuel for orbital flight of payloads that can tolerate higher g-forces; consequently reduced stratospheric emissions of water vapour that otherwise present an AGW issue; simplicity resulting in greatly reduced costs for launch; and avoidance of risks to expensive payloads until active parts of the system are in place. Other risks such as fuel explosions are removed completely.

The journey comprises two parts: the first part towards the first parachute conveys high vertical speed while the second part converts most of this to horizontal speed while continuing acceleration. The projectile therefore acquires very high horizontal speed required for sub-orbital and potentially for orbital missions.

The technique is intended mainly for the mid-term and long-term future, since it only comes into its own once it becomes possible to economically make graphene components such as strings, strong rings and tapes, but short term use is feasible with lower but still useful specifications based on interim materials. While long term launch of people-carrying rockets is feasible, shorter term uses would be limited to smaller payloads or those capable of withstanding higher g-forces. That makes it immediately useful for some satellite or military launches, with others quickly becoming feasible as materials improve.

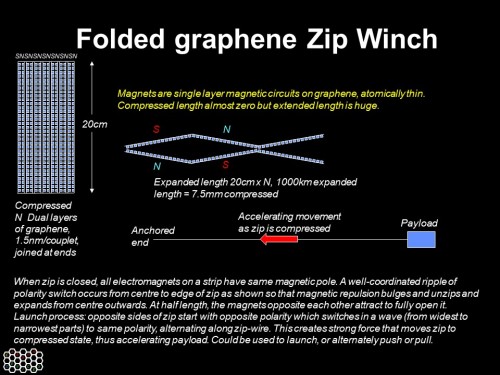

Either of two mechanisms may be used for drawing the cable – a drum based reel or a novel electromagnetic cable drive system. The drum variant may be speed limited by the strength of drum materials, given very high centrifugal forces. The electromagnetic variant uses conventional propulsion techniques, essentially a linear motor, but in a novel arrangement so is partly unproven.

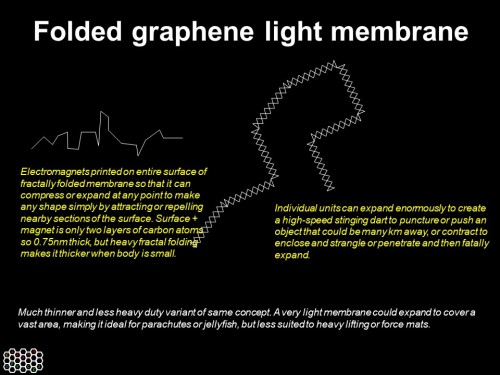

There are also alternative methods available for parachute deployment and management. One is to make the parachutes from lighter-than-air materials, such as graphene foam, which is capable of making solid forms less dense than helium. The chutes would float up and be pulled into their launch positions. A second option is to use helium balloons to carry them up, again pulling them into launch positions. A third is to use a small rocket or even two to deploy them. Far future variants will probably opt for lighter-than-air parachutes, since they can float up by themselves, carry additional tethers and equipment, and can remain at high altitude to allow easy reuse, floating back up after launch.

There are many potential uses and variants of the system, all using the same principle of temporary high-atmosphere anchors, aerodynamically restricted to useful positions during launch. Not all are discussed here. Although any hypersonic launch system has potential military uses, civil uses to reduce or eliminate fuel requirements for space launch for human or non-human payloads are by far the most exciting potential as the Sling will greatly reduce the currently prohibitive costs of getting people and material into orbit. Without knowing future prices for graphene, it is impossible to precisely estimate costs, but engineering intuition alone suggests that such a simple and re-usable system with such little material requirement ought to be feasible at two or three orders of magnitude less than current prices, and if so, could greatly accelerate mid-century space industry development.

Formal articles in technical journals may follow in due course that discuss some aspects of the sling and catapult systems, but this article serves as a simple publication and disclosure of the overall system concepts into the public domain. Largely reliant on futuristic materials, the systems cannot reasonably be commercialised within patent timeframes, so hopefully the ideas that are freely given here can be developed further by others for the benefit of all.

This is not intended to be a rigorous analysis or technical specification, but hopefully conveys enough information to stimulate other engineers and companies to start their own developments based on some of the ideas disclosed.

Introductory Background

A large number of non-fuel space launch systems have been proposed, from Jules Verne’s 1865 Moon gun through to modern railguns, space hooks and space elevators. Rail guns convey moderately high speeds in the atmosphere where drag and heating are significant limitations, but their main limitation is requiring very high accelerations but still achieving too low muzzle velocity for even sub-orbital trips. Space-based tether systems such as space hooks or space elevators may one day be feasible, but not soon. Current space launches all require rockets, which are still fairly dangerous, and are highly expensive. They also dump large quantities of water vapour into the high atmosphere where, being fairly persistent, it contributes significantly to the greenhouse effect, especially as it drifts towards the poles. Moving towards using less or no fuel would be a useful step in many regards.

The Pythagoras Sling

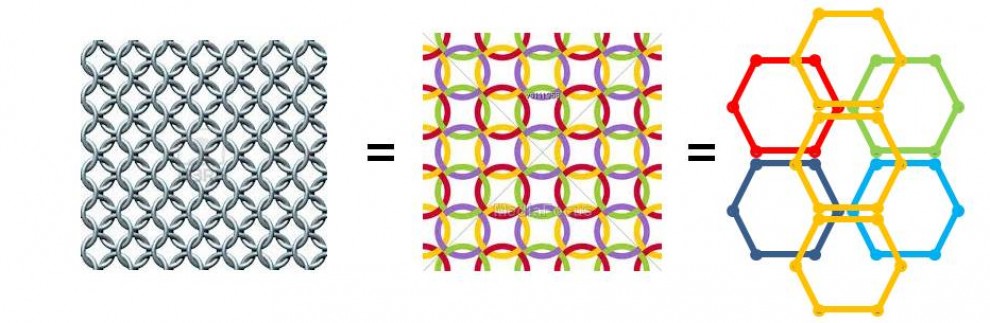

In summary, having considered many potential space launch mechanisms based on high altitude platforms or parachutes, by far the best system is the Pythagoras Sling. This uses two high-altitude parachutes attached to rings, offering enough drag to act effectively as temporary slow-moving anchors while a tether is pulled through them quickly to accelerate a projectile upwards and then into a curve towards final high horizontal speed.

We called this approach the Pythagoras Sling due to its simplicity and triangular geometry. It comprises some ground equipment, two large parachutes and a length of string. The parachutes would ideally be made using lighter-than-air materials such as graphene foam, a foam of tiny graphene spheres containing vacuum, that is less dense than helium. They could therefore float up to the required altitude, and could be manoeuvred into place immediately prior to launch. During the launch process they would move so it would take a few hours to float back to their launch positions. They could remain at high altitude for long periods, perhaps permanently. In that case, as well as carrying the tether for the launch, additional tethers would be needed to anchor and manoeuvre the parachutes and to feed launch tether through in preparation for a new launch. It is easy to design the system so that these additional maintenance tethers are kept well out of the way of the launch path.

The parachutes could be as large as desired if such lightweight materials are used, but if alternative mechanisms such as rockets or balloons are used to carry them into place, they would probably be around 50m diameter, similar to the Mars landing ones.

Each parachute would carry a ring through which the launch tether is threaded, and the rings would need to be very strong, low friction, heat-resistant and good at dispersing heat. Graphene seems an ideal choice but better materials may emerge in coming years.

The first parachute would float up to a point 60-80km above the launch site and would act as the ‘sky anchor’ for the first phase of launch where the payload gathers vertical speed. The 2nd parachute would be floated up and then dragged (using the maintenance tether) as far away and as high as feasible, but typically to the same height and 150km away horizontally, to act as the fulcrum for the arc part of the flight where the speed is both increased and converted to horizontal speed needed for orbit.

Simulation will be required to determine optimal specifications for both human and non-human payloads.

Another version exists where the second parachute is deployed from a base with winding equipment 150km distant from the initial rocket launch. Although requiring two bases, this variant holds merit. However, using a single ground base for both chute deployments offers many advantages at the cost of using slightly longer and heavier tether. It also avoids the issue that before launch, the tether would be on the ground or sea surface over a long distance unless additional system details are added to support it prior to launch such as smaller balloons. For a permanent launch site, where the parachutes remain at high altitude along with the tethers, this is no longer an issue so the choice may be made on a variety of other factors. The launch principle remains exactly the same.

Launch Process

On launch, with the parachutes, rings and tethers all in place, the tether is pulled by either a jet engine powered drum or an electromagnetic drive, and the projectile accelerates upwards. When it approaches the first parachute, the tether is disengaged from that ring, to avoid collision and to allow the second parachute to act as a fulcrum. The projectile is then forced to follow an arc, while the tether is still pulled, so that acceleration continues during this period. When it reaches the final release position, the tether is disengaged, and the projectile is then travelling at orbital or suborbital velocity, at around 200km altitude. The following diagram summarises the process.

Two-base variant

This variant with two bases and using rocket deployment of the parachutes still qualifies as a Pythagoras Sling because they are essentially the same idea with just minor configurational differences. Each layout has different merits and simulation will undoubtedly show significant differences for different kinds of missions that will make the choice obvious.

Calculations based on graphene materials and their theoretical specifications suggest that this could be quite feasible as a means to achieve sub-orbital launches for humans and up to orbital launches for smaller satellites that can cope with 15g acceleration. Other payloads would still need rockets to achieve orbit, but greatly reduced in size and cost.

Exchanges of calculations between the authors, based on the best materials available today suggest that this idea already holds merit for use for microsatellites, even if it falls well below graphene system capabilities. However, graphene technology is developing quickly, and other novel materials are also being created with impressive physical qualities, so it might not be many years before the Sling is capable of launching a wide range of payload sizes and weights.

In closing

The Pythagoras Sling arose after several engineering explorations of high-altitude platform launch systems. As is often the case in engineering, the best solution is also by far the simplest. It is the first space launch system that treats parachutes effectively as temporary aerial anchors, and it uses just a string pulled through two rings held by those temporary anchors, attached to the payload. That string could be pulled by a turbine or an electromagnetic linear motor drive, so could be entirely electric. The system would be extremely safe, with no risk of fuel explosions, and extremely cheap compared to current systems. It would also avoid dumping large quantities of greenhouse gases into the high atmosphere. The system cannot be built yet, and its full potential won’t be realised until graphene or similarly high specification strings or tapes are economically available. However, it should be well noted that other accepted future systems such as the Space Elevator will also need such materials, but in vastly larger quantity. The Pythagoras Sling will certainly be achievable many years before a space elevator and once it is, could well become the safest and cheapest way to put a wide range of payloads into orbit.