A rail gun is a simple electromagnetic motor that very rapidly accelerates a metal slug by using it as part of an electrical circuit. A strong magnetic field arises as the current passes through the slug, propelling it forwards.

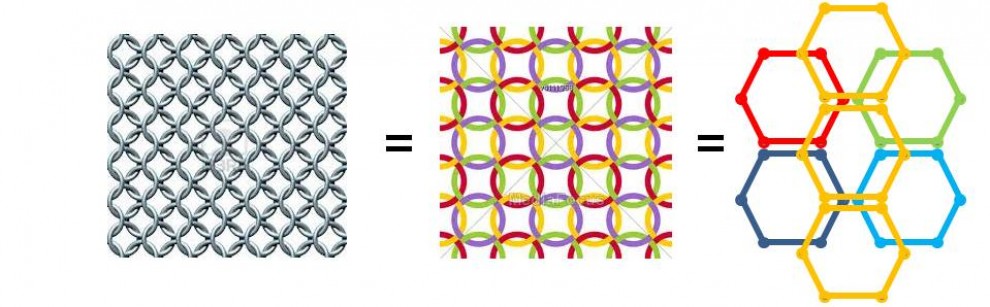

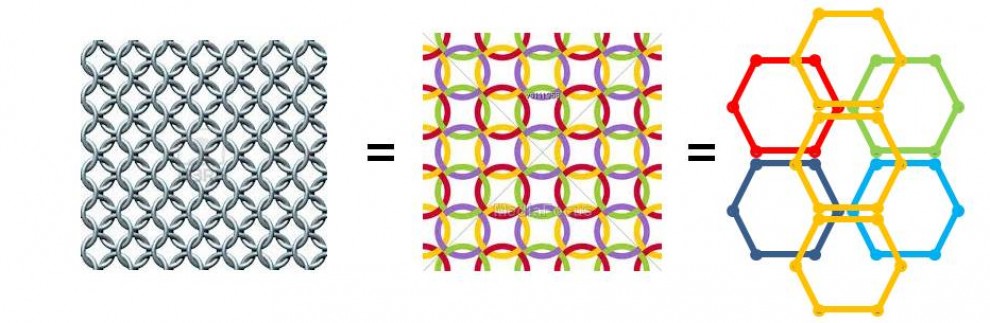

An ‘inverse rail gun’ uses the same principle, but rather than a short slug, the force acts on a small section of a long cable, which continues to pass through the system. As that section passes through, another takes its place, passing on the force and acceleration to the remainder of the cable. That also means that each small section only has a short and tolerable time of extreme heating resulting from high current.

This can be used either to accelerate a cable, optionally with a payload on the end, or via Newtonian reaction, to drag a motor along a cable, the motor acting as a sled, accelerating all along the cable. If the cable is very long, high speeds could result in the vacuum of space. Since the motor is little more than a pair of conductive plates, it can easily be built into a simple spacecraft.

A suitable spacecraft could thus use a long length of this cable to accelerate to high speed for a long distance trip. Graphene being an excellent conductor as well as super-strong, it should be able to carry the high electric currents needed in the motor, and solar panels/capacitors along the way could provide it.

With such a simple structure, made from advanced materials, and with only linear electromagnetic forces involved, extreme speeds could be achieved.

A system could be made for trips to Mars for example. 10,000 tons of sufficiently strong graphene cable to accelerate a 2 ton craft at 5g could stretch 6.7M km through space, and at 5g acceleration (just about tolerable for trained astronauts), would get them to 800km/s at launch, in 4.6 hours. That’s fast enough to get to Mars in 5-12 days, depending where it is, plus a day each end to accelerate and decelerate, 7-14 days total.

10,000 tons is a lot of graphene by today’s standards, but we routinely use 10,000 tons of steel in shipbuilding, and future technology may well be capable of producing bulk carbon materials at acceptable cost (and there would be a healthy budget for a reusable Mars launch system). It’s less than a space elevator.

6.7M km is a huge distance, but space is pretty empty, and even with gravitation forces distorting the cable, the launch phase can be designed to straighten it. A shorter length of cable on the opposite side of an anchor (attached to a Moon tower, or a large mass at a Lagrange point) would be used to accelerate the spacecraft towards the launch end of the cable, at relatively low speed, say 100km/s, a 20 hour journey, and the deceleration phase of that trip applies significant force to the cable, helping to straighten and tension it for the launch immediately following. The craft would then accelerate along the cable, travel to Mars at high speed, and there would need to be an intercept system there to slow it. That could be a mirror of the launch system, or use alternative intercept equipment such as a folded graphene catcher (another blog).

Power requirements would peak at the very last moments, at a very high 80GW. Then again, this is not something we could build next year, so it should be considered in the context of a mature and still fast-developing space industry, and 800km/s is pretty fast, 0.27% of light speed, and that would make it perfect for asteroid defense systems too, so it has other ways to help cost in. Slower systems would have lower power requirements or longer cable could be used.

Some tricky maths is involved at every stage of the logistics, but no more than any other complex space trip. Overall, this would be a system that would be very long but relatively low in mass and well within scales of other human engineering.

So, I think it would be hard, but not too hard, and a system that could get people to Mars in literally a week or two would presumably be much favored over one that takes several months, albeit it comes with some serious physical stress at each end. So of course it needs work and I’ve only hinted superficially at solutions to some of the issues, but I think it offers potential.

On the down-side, the spaceship would have kinetic energy of 640TJ, comparable to a small nuke, and that was mainly limited by the 5g acceleration astronauts can cope with. Scaling up acceleration to 1000s of gs military levels could make weapons comparable to our largest nukes.