We’re hearing much more lately about stakeholders, greenwashing, wokewashing, UBI and lots of other things that were rarely mentioned in the corporate world until fairly recently, as well as the eternal anticapitalist background noise companies seem always to have lived under. I’ve written about some of these things over the years, but it seems a good time to bring it together.

It’s hard to be precise about when these things appeared, but wokeness is really just political correctness with added Newspeak. PC has been around (noticeably) since the early 90s and evolved into wokeness maybe 5 years ago. I first saw greenwashing around 2000 and UBI around 2012 (though the idea existed long before that). The idea of stakeholders rather than just shareholders also goes back to at least the early 90s, or at least that’s when it first appeared in anything I wrote.

The strongest anchor I have relied on during my futurologist career is human nature, which has changed little probably for 100,000 years and is unlikely change much until genetic modification starts to significantly impact on personality (towards the end of this century). So at least until 2050, while activists seem to assume everyone will readily adopt their wonderful new ideas, filtering their wish-lists through human nature usually identifies many items as having limited appeal and short term impacts at best. The best and most familiar example is communism, which is always presented as a lovely utopian ideal that appeals strongly to teenage minds, but a few seconds thought by anyone with adult experience of the world shows exactly why it never works well. I don’t need to repeat the details because you know them well, but similar experience-based reasoning relying on human nature also lends itself to quickly dismiss any ideas that we have somehow moved beyond tribalism, selfishness, greed and envy or religiosity. I’ve written many blogs about tribalism.

Capitalism has proved over many decades that human nature is a solid business foundation. People want to improve their quality of life, to gain wealth and power, and to a lesser extent, to extend these benefits to their families, friends and tribe (in that order). They will happily work hard and take risks to achieve these goals. Outsiders with less can be equally relied on to look on enviously, and to attempt to limit or control those gains and to demand they are shared. Modern democracies have all implemented platforms that divide risks and rewards between capitalist protagonists and wider society, with different political offering different balances.

For many decades, that balance was implemented through the tax system, with regulation limiting potential harm during the wealth generation process. Subject to such regulation, companies were intended solely to generate profit for shareholders and taxes for government.

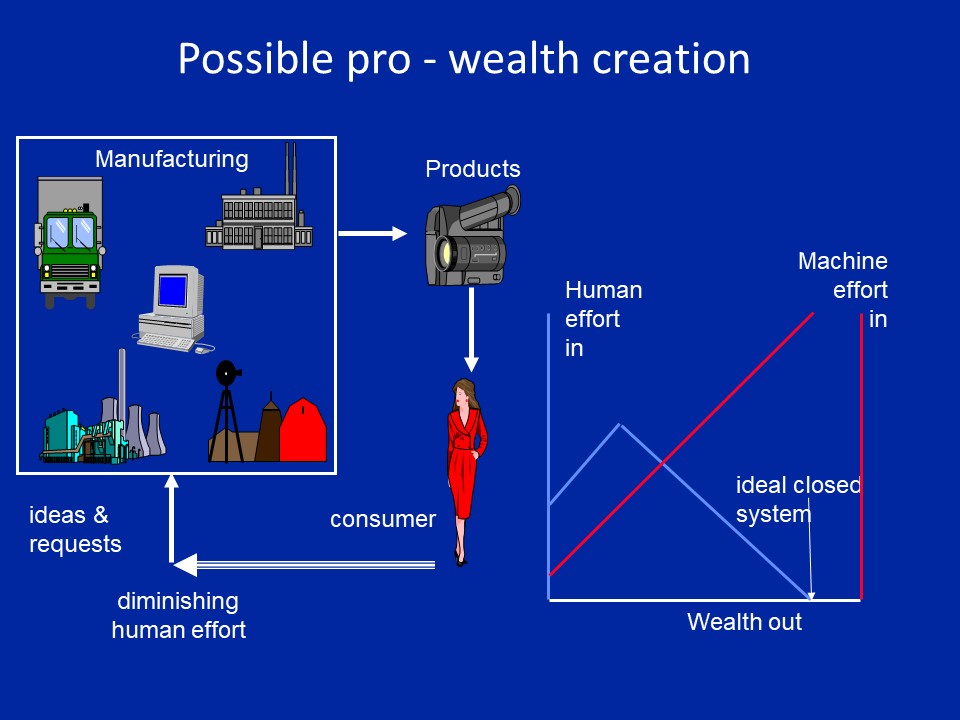

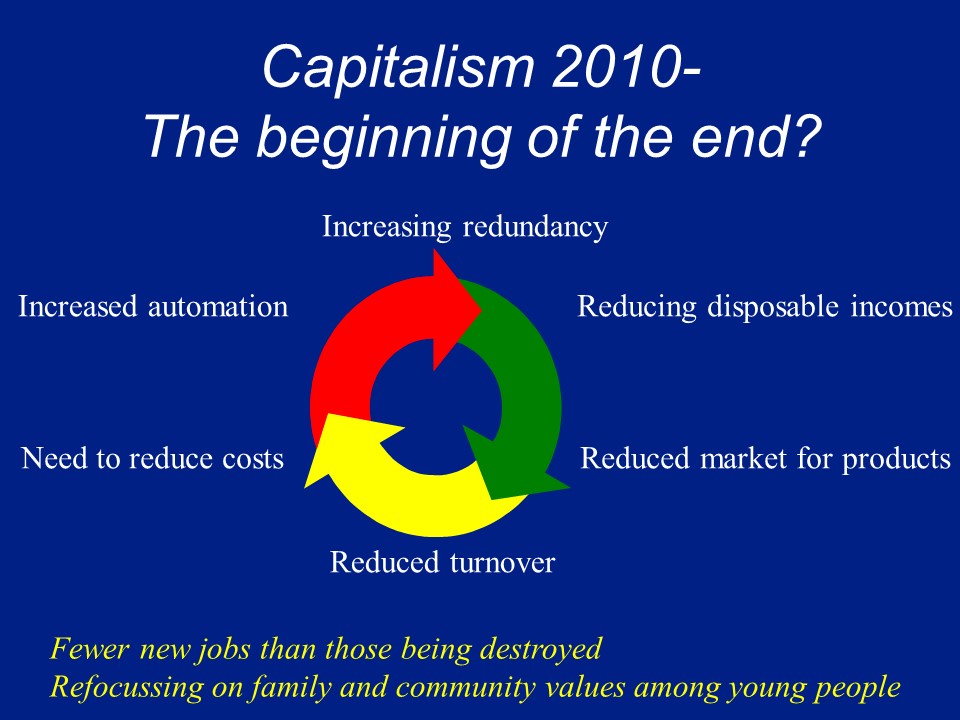

From the onset of automation and its potential to spread, it has been obvious that a far future company might need very few workers, thus concentrating wealth. In the early 90s, the idea of the ‘fly-by-wire society’ emerged where machines would do most work and people could have a leisurely existence. Some ancient slides; the reference to 2010 demonstrates I thought the beginning of the end for pure capitalism could happen earlier than it has – only in the last few years has debate moved that direction:

The problem is obvious (and we have recently heard billionaires explain it), that if all the money gets concentrated in the accounts of just a few people, the rest of us wouldn’t be able to afford the products so the system would grind to a halt. Only by redistributing enough of the wealth somehow could the profit stream be maintained. Hence the idea of universal basic income, UBI, where we’d all be paid a wage just for existing, so that we can still buy stuff and keep demand high.

The most obvious problem with UBI is that if it is high enough, many people won’t want to work and become stupid, lazy and unhealthy, while others who have to work may become resentful that others are paid to do nothing. As in communism, the workers would gradually become unreliable, unproductive and offer poor customer service and poor products.

So while it is obvious that ever-increasing automation requires some tweaking of the fundamentally sound capitalist model, there are many potential pitfalls in the immediately obvious solutions. Nevertheless, we will still need those tweaks, and if not UBI, then a close genetically modified relative. UBI 2.0 then, to avoid working out the details yet.

Looking again at the foundations of the capitalist model, we see that people are willing to work, invest and take risks in return for likely rewards. On an imaginary future spaceship, inhabited only by people leaving the world to make their own way in the universe, those people may arguably be free to do as they wish, how they wish and to keep all the proceeds to themselves. While people share the same planet, to ensure that they can do so safely and without the resistance of others, there will inevitably need to be some restrictions on their activities. Taxation is a quite separate consideration, that takes us naturally to introducing stakeholders.

Stakeholders are any parties who hold any kind of stake in an enterprise – providers of capital, land and resources needed to get the enterprise up and running, workers, their families and friends, nearby society, local, national, regional and global government, consumers, and representatives of the environment, even people who have to see the buildings as they drive past. That’s the usual list that we see all the time, but it has serious omissions. The key missing factor is that all enterprises are built on shared foundations of shared human culture, invention, and infrastructure and that means that everyone in society is a co-investor alongside the capitalist money-suppliers. We all build on the myriad contributions of our ancestors since the Stone Age. If we look at society, rightfully, as a co-investor, the idea of sharing rewards with wider society stops being seen as a charitable act and taxation is not theft, but rightful sharing of rewards among investors. That is very different from the current company model.

I have re-used my blog piece about culture tax a few times now, but here it is again:

When someone creates and builds a company, they don’t do so from a state of nothing. They currently take for granted all our accumulated knowledge and culture – trained workforce, access to infrastructure, machines, governance, administrative systems, markets, distribution systems and so on. They add just another tiny brick to what is already a huge and highly elaborate structure. They may invest heavily with their time and money but actually when considered overall as part of the system their company inhabits, they only pay for a fraction of the things their company will use.

That accumulated knowledge, culture and infrastructure belongs to everyone, not just those who choose to use it. It is common land, free to use, today. Businesses might consider that this is what they pay taxes for already, but that isn’t explicit in the current system.

The big businesses that are currently avoiding paying UK taxes by paying overseas companies for intellectual property rights could be seen as trailblazing this approach. If they can understand and even justify the idea of paying another part of their company for IP or a franchise, why should they not pay the host country for its IP – access to the residents’ entire culture?

This kind of tax would provide the means needed to avoid too much concentration of wealth. A future businessman might still choose to use only software and machines instead of a human workforce to save costs, but levying taxes on use of the cultural base that makes that possible allows a direct link between use of advanced technology and taxation. Sure, he might add a little extra insight or new knowledge, but would still have to pay the rest of society for access to its share of the cultural base, inherited from the previous generations, on which his company is based. The more he automates, the more sophisticated his use of the system, the more he cuts a human workforce out of his empire, the higher his taxation. Today a company pays for its telecoms service which pays for the network. It doesn’t pay explicitly for the true value of that network, the access to people and businesses, the common language, the business protocols, a legal system, banking, payments system, stable government, a currency, the education of the entire population that enables them to function as actual customers. The whole of society owns those, and could reasonably demand rent if the company is opting out of the old-fashioned payments mechanisms – paying fair taxes and employing people who pay taxes. Automate as much as you like, but you still must pay your share for access to the enormous value of human culture shared by us all, on which your company still totally depends.

Linking to technology use makes good sense. Future AI and robots could do a lot of work currently done by humans. A few people could own most of the productive economy. But they would be getting far more than their share of the cultural base, which belongs equally to everyone. In a village where one farmer owns all the sheep, other villagers would be right to ask for rent for their share of the commons if he wants to graze them there.

I feel confident that this extra tax would solve many of the problems associated with automation. We all equally own the country, its culture, laws, language, human knowledge (apart from current patents, trademarks etc. of course), its public infrastructure, not just businessmen. Everyone surely should have the right to be paid if someone else uses part of their share. A culture tax would provide a fair ethical basis to demand the taxes needed to pay UBI 2.0 so that all may prosper from the coming automation.

The extra culture tax would not magically make the economy bigger, though automation may well increase it a lot. The tax would ensure that wealth is fairly shared. Culture tax/UBI duality is a useful tool to be used by future governments to make it possible to keep capitalism sustainable, preventing its collapse, preserving incentive while fairly distributing reward. Without such a tax, capitalism simply may not survive.

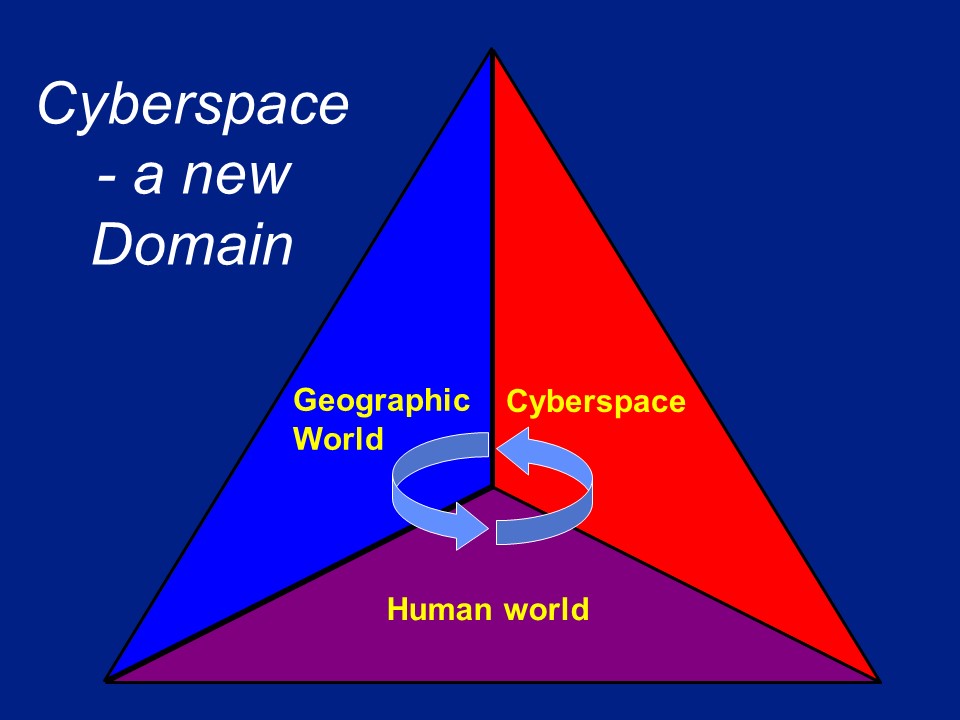

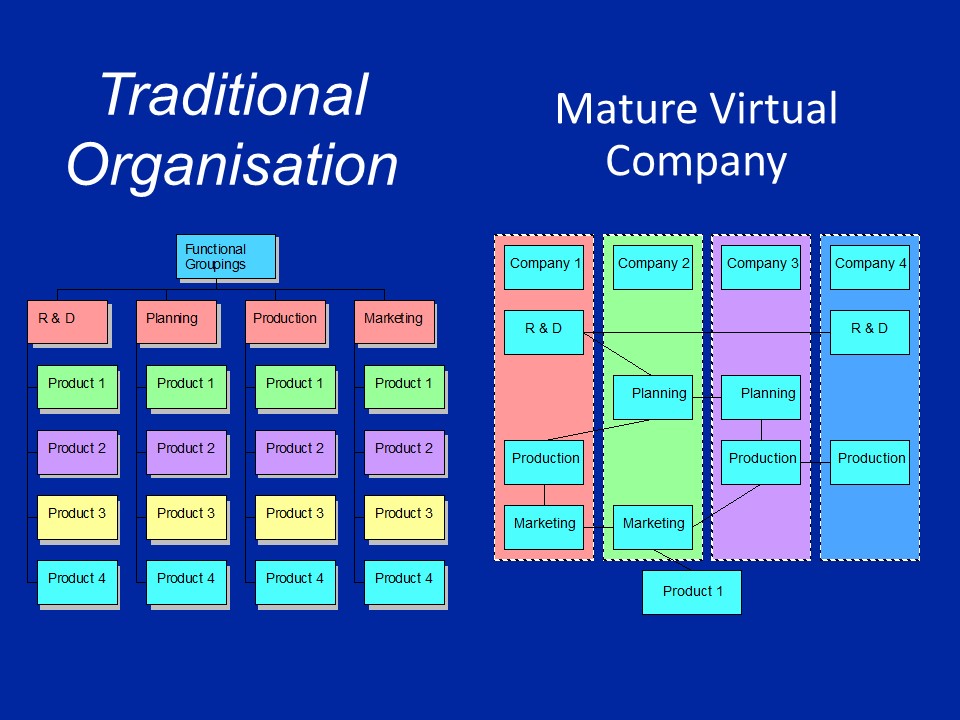

Now bring in the recent enthusiastic talk about the Metaverse and virtual companies. Neither is a new idea. Here are some 1992 pics wot I did based on common thinking in IT then:

Work-from-anywhere roaming teleworkers would work on short-term projects with anyone appropriate anywhere in the world, including AI/robots. At the same time, we already understood one of the biggest problems we already see from global organisations, that of limited jurisdiction, both of regulators and the taxman, and also how NGOs and pressure groups might respond.

It’s surprising that 30 years on, we don’t already see the use of such smart emails, which would be far more effective weapons that twitter cancellations in attacking rogue companies’ bottom lines.

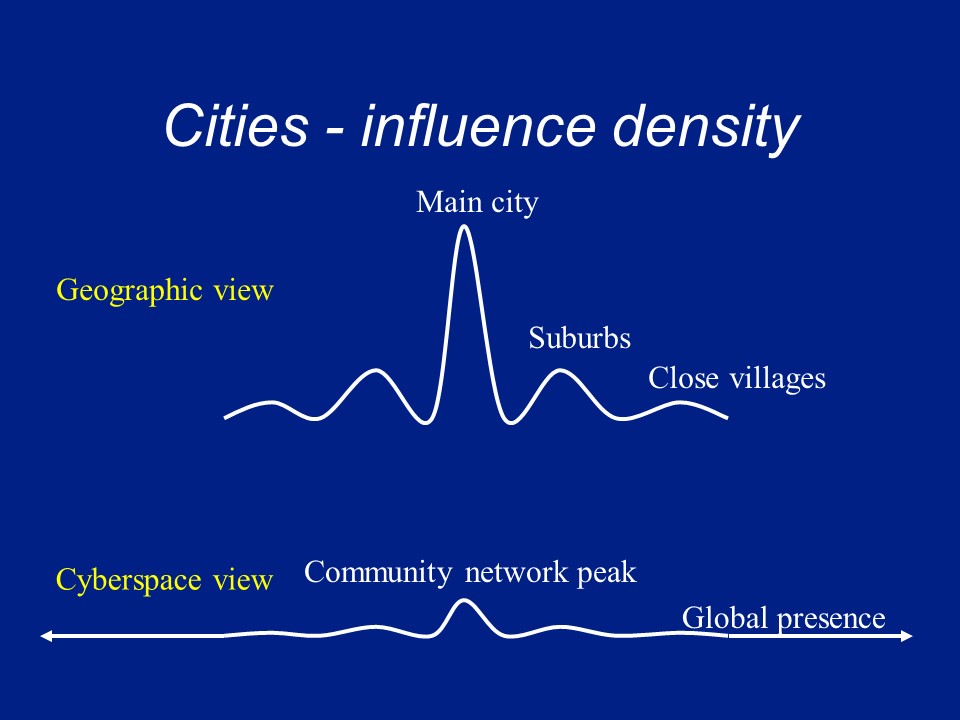

If we re-introduce human nature to this model, we see another common feature of social media, tribalism, where large numbers of people spread around the world, are able to coordinate efforts as if they were all together. Tribalism has never been about geographic proximity and will manifest in cyberspace just as strongly. Even cities, with their particular tribal identity and culture, can morph into global tribal influences:

So it is very clear firstly that there are many stakeholders that can rightfully lay claim to share in the nature and governance of companies, and share their risks, their outputs and profits, and secondly that there are potentially powerful mechanisms that can pressure companies to behave even if they are outside the geographical jurisdiction of any particular government. Virtual companies may be able to step outside national boundaries, but so can any virtual NGO. National governments may not be able to act, but the people they represent certainly can wield their combine power just as effectively in a virtual world.

I believe what we are missing is the shared realisation of our common status as stakeholders in every enterprise. We have become too used to companies being owned and run entirely by their financers, too willing to let them get away with using an old model even though the world has changed dramatically. That model was perfect when companies operations were resident entirely within a nation’s boundaries, because the nation benefited appropriately from its operations, sufficiently to compensate for the shared cultural and intellectual investment. It is simply no longer appropriate model in a world where companies can offshore parts of operations to purloin the share of profits that rightfully belong to its host societies.

I’m no anti-capitalist, and certainly no communist, but even I can see that it is time to redraft the social contract defining companies and how they relate to the world they operate in. All stakeholders need to be recognised, and each to be attributed their rightful share of both the risks and proceeds.

There will be a lot of talk of stakeholders over the next few years. It isn’t all socialist nonsense, though there will undoubtedly be lots of that. It really is time to rebalance the law in favour of the little people.