This blog is an extract from my book Total Sustainability. Just over 10k words

Sustainable capitalism

To see what needs adjusted and how to go about doing it, let’s first consider some of the systems that make people wealthy. With global change accelerating, in this period of global upheaval, the rise of new powers and decline of old ones, we have an opportunity to rethink it and perhaps make it better, or perhaps countries new to capitalism will make their own way and we will follow. If it is failing, it is time to look for ways to fix it or to change direction.

Some things are very difficult and need really smart people, but we don’t have very many of them. But as heavily globalised systems become more and more complex, the scope for very smart people to gain control of power and resources increases. Think about it for a moment. How many people do you know who could explain how big businesses manage to avoid paying tax in spite of making big profits beyond the first two words that everyone knows – tax haven? The money goes somewhere, but not on tax. This is one of the big topics being discussed now among the world’s top nations. No laws are being broken, it is simply that universally sluggish and incompetent governments have been outwitted again and again by smart individuals.

They should have had tax systems in place long ago to cope with globalisation, but they still haven’t. Representatives of those governments talk a lot about clampdowns, but nobody really expects that big business won’t stay at least 5 steps ahead. Consequently, money and power is concentrating at the top more than ever.

The contest between greedy and relatively smart business people and well-meaning but dumber (strictly relative terms here) politicians and regulators often ends with taxpayers being fleeced. Hence the banking crisis, where the vast wealth greedily that was accumulated by bankers over numerous gambling wins was somehow kept when they lost, with us having to pay the losses without ever benefiting from the wins, with the final farcically generous pay-offs to those who failed so miserably. The same could be said of some privatisations and probably most government contracts. It was noted thousands of years ago that a fool and his money are easily parted. The problem with democracy is that fools are often the ones elected. The people in government that aren’t fools are often there to benefit their own interests and later found with their fingers in the cake. Some of our leaders and regulators are honourable and smart enough to make decent decisions, but too small a fraction to make us safe from severe abuse.

We need to fix this problem and many other related if we are to achieve any form of sustainability in our capitalist world.

Magistrates in Britain once had a duty to distinguish between the deserving poor, who were poor through no fault of their own, and the undeserving poor, who were simply idle. The former would get hand-outs while they needed them, the idle would get a kick in the pants and told to go and sort themselves out. This attitude later disappeared from the welfare system, but the idea remains commonly held and recently, some emerging policies echo its sentiment to some degree.

Looking at the other end of the spectrum, there are the deserving and undeserving rich. Some people worked hard to get their cash and deserve every penny, some worked less hard in highly overpaid jobs. Some inherited it from parents or ancestors even further back, and maybe they worked hard for it. Some stole it from others by thievery, trickery, or military conquest. Some got it by marrying someone. Some won it, some were compensated. There are lots of ways of getting rich. Money is worth the same wherever it comes from but we hold different attitudes to the rich depending on how they got their money.

Most of us don’t think there is anything wrong with being rich, nor in trying to become so. There are examples of people doing well not just for themselves and their families and friends, but also benefiting their entire host community. Only jealousy could motivate any resentment of their wealth. But the system should be designed so that one person shouldn’t be able to become rich at the cost of other people’s misery. At the moment, in many countries, some people are gaining great wealth effectively by exploiting the poor. Few of us consider that to be admirable or desirable. It would be better if people could only become rich by doing well in a system that also protects other people. Let’s look at some of the problems with today’s capitalism.

Corruption has to be one of the biggest problems in the world today. It has many facets, and some are so familiar in everyday life that we don’t even think of them as corruption any more.

As well as blatant corruption, most of us would also include rule bending and loophole-seeking in the corruption category. Squeezing every last millimetre when bending the law may keep it just about legal, but it doesn’t make behaviour creditable. When we see politicians bending rules and then using their political persuasiveness to argue that it is somehow OK for them, most of us feel a degree of natural revulsion. The same goes for big companies. It may be legal to avoid tax by using expensive lawyers to find holes in taxation systems and clever accountants to exploit them, re-labelling or moving money via a certain route to reduce the taxes required by law, but that doesn’t make it ethical. Even though it is technically on the right side of legal, I’d personally put a lot of corporate tax avoidance in the corruption category when it seeks to exploit loopholes that were never part of what the tax law intended.

Then of course it is possible to break the law and bribe your way out of trouble, or to lobby corruptible lawmakers to include a loophole that you want to exploit, or to make a contribution to party funds in order to increase the likelihood of getting a big contract later.

Lobbying can easily become thinly veiled bribery – nice dinners or tickets or promised social favours, but often manifests as well-paid clever chitchat, to get an MP to help push the law in the general direction you favour. Maybe it isn’t technically corrupt, but it certainly isn’t true to the basic principles of democracy either. Lobbying distorts the presentation, interpretation and implementation of the intentions of the voting community so it corrupts democracy.

So although there are degrees of corruption, they all have one thing in common – using positions of power or buy influence to tilt the playing field to gain advantage.

Once someone starts bending the rules, it affects other behaviour. If someone is happy exploiting the full flexibility of the letter of the law with little regard for others, they are also likely to be liable to engage in other ways of actively exploiting other people, in asset stripping, or debt concealing, or in how they negotiate and take advantage, or how they make people redundant because a machine is cheaper. It is often easy to spot such behaviour, wrapped with excuses such as ‘Companies aren’t charities, they exist to make money’, and ‘business is business’. There are plenty of expressions that the less noble business people use to excuse bad behaviour and pretend it is somehow OK. There are degrees of badness of course. For some companies, some run by people hailed as business heroes, anything goes as long as it is legal or if the process of law can be diverted long enough to make it worthwhile ignoring it. While ‘legal’ depends on the size and quality of your legal team, there is gain to be made by stretching the law. It can even pay to blatantly disobey the law, if you can stretch the court process out enough so that you can use some of the profits gained to pay the fines, and keep the rest. So corruption isn’t the only problem. Exploitation is its ugly sister and we see a lot of big companies and rich people doing it.

The price of bad behaviour and loose values

A common problem here is that we don’t assign financial value to honourable behaviour, community or national well-being, honesty, integrity, fairness or staff morale. So these can safely be ignored in the pursuit of profit. Business is justified in this approach perhaps, because we don’t assign value to them. If a company exists to make profit, measured purely financially, those other factors don’t appear on the bottom line, so there is no reason to behave any better. In fact, they cost money, so a ruthless board can make more money by behaving badly. That is one thing that could and should change if we want a sustainable form of capitalism. If we as a society want businesses to run more ethically, then we have to make the system in such a way that ethical behaviour is rewarded. If we don’t explicitly recognise particular value sets, then businesses are really under no obligation to behave in any particular way. As it is, I would argue that society has value sets that are on something of a random walk. There is no fixed reference point, and values can flip completely in just a few decades. That is hardly a stable platform on which to build anything.

Hardening of attitudes to welfare abuse

There is growing resentment right across the political spectrum against those taking welfare who won’t do enough to try to look after themselves but expect to receive hand-outs while others are having to work hard to make ends meet. At the same time, resentment is deepening against the rich who use loopholes in the law to find technically legal but morally dubious tax avoidance schemes. What these have in common is that they exploit others. There is a rich variety of ways in which people exploit others, some that we are so used to we don’t even notice any more. This is important in helping to determine what may happen in the future.

The few have always exploited the many

A while ago, I had a short break visiting the Cotswolds (a chocolate-box picture area of England). We saw a huge Roman villa, fantastic mosaics in the Roman museum in Cirencester, and a couple of stately homes. Then we went to Portugal where we saw the very ornate but rather tasteless Palace of Penna. It made me realise just how much better off we are today, when thanks to technology development, even a modest income buys vastly superior functionality and comfort than even royalty used to have to put up with.

I used to enjoy seeing such things, but the last few years I have found them increasingly disturbing. I still find them interesting to look at, but now they make me angry, as monuments to the ability of the few to exploit the efforts of the many for their own gain. So while admiring the landscape architecture of Lancelot (Capability) Brown, and the Roman mosaics, I felt sorry for the many people who had little or no choice but to do all the work for relatively little reward. I felt especially sorry for the people who built the Palace of Penna, where an obviously enormous amount of hard work and genuine talent has been spent on something that ended up as hideously ugly. Even if the artists and workmen were paid a good wage, their abilities could probably still have been put to much more constructive use.

But we don’t want equality of poverty

I strongly believe that we overvalue capital compared to knowledge, talent and effort, resulting in too high a proportion of wealth going to capital owners. Capitalism sometimes saps too many of the rewards of effort away from those who earn them. However, few people would argue for a system where everyone is poorer just so that we can have equality, as happened in communism, and as would be the result if some current socialists got their ways. The system should be fair to everyone, but if we are to prosper as a society, it also needs to incentivise the production of wealth.

Exploitation of society by the lazy and greedy

That of course brings us to the abuse at the other end, with some people who are perfectly able to work drawing state benefits instead (or indeed as well as wages from work) and thereby putting unjust extra load on the welfare system. This of course acts as a major drain on hard working people too and reduces the rewards of effort. Those who work hard may thus see their money disappearing at both ends, possibly taken by exploitative employers and certainly taken by the state to give to others. Exploitation is still exploitation whether it is by the privileged or the lazy. We all want the welfare system, because another powerful force in human nature is to care for others, and we instinctively want to help those who can’t help themselves. But that doesn’t mean we want to be taken advantage of.

Rewarding effort is essential for a healthy economy

As a general principle, extra effort or skill or risk or investment should reap extra reward. If there is too little incentive to do put in more work or investment, human nature dictates that most people won’t do it. The same goes for leading others or building companies and employing others. If you don’t get extra reward from enabling or leading other people to create more, you probably won’t bother doing that either. Very many communes have started up with idealism and failed for this reason.

In both of these cases, a few nice people will do more, even without financial incentive, simply because it makes them feel good to work hard or help others, but most won’t, or will start doing so and quickly give up when appreciation runs dry or they become frustrated by the laziness of others.

While effort and investment and skill and leadership must all be rewarded to make a healthy economy, it is a natural and fair consequence of rewarding these that some people will become richer than others, and if they help many other people also to do more, they may become quite a lot richer than others.

‘To each according to their effort’ is a fundamentally better approach than ‘from each according to their ability and to each according to their need’ as preached by communists – it is simply more in tune with human nature. It makes more people do more, so we all prosper. Trying to level the playing field by redistributing wealth too much deters effort and ultimately makes everyone worse off. A reasonable gap between rich and poor is both necessary and fair.

But we shouldn’t let people demand too much of the rewards

However, an extreme gap indicates that there is exploitation, that some people are keeping rather too much of the reward from the efforts of others. As always, we need to find the right balance. Greed does seem to be one of the powerful forces in human nature, and if opportunity exists for someone to take more for themselves at the expense of others, some will. I don’t believe we should try to change human nature, but I do believe we should try to defend the weak against exploitation by the greedy. Some studies have shown a correlation between social inequality and social problems of crime, poor education and so on. That doesn’t prove causality of course, but it does seem reasonable to infer causality in any case here.

In some large companies, top managers seem to run the company as if it were their own, allocating huge rewards for themselves at the expense of both customers and shareholders’ interests. Such abuse of position is widespread across the economy today, but it will inevitably have to be reined back over time in spite of fierce resistance from the beneficiaries.

The power of public pressure via shame should not be underestimated, even though some seem conspicuously immune to it. Where the abusers still decide to abuse, power will come either by shareholders disposing of abusers, or regulators giving shareholders better power to over-rule where there is abuse, as is already starting to happen, or by direct pay caps for public sector chiefs. The situation at the moment gives too much power to managers and shareholders need to be given back the rights to control their own companies more fully.

Reducing market friction

There are many opportunities to exploit others, and always some who will try to take the fullest advantage. We can’t ever make everyone nice, but at least we can make exploitation more difficult. Part of the problem is social structure and governance of course, but part is also market imperfection. While social structure only changes slowly, and government is doomed to suffer the underlying problems associated with democracy, we can almost certainly do something about the market using better technology. So let’s look at the market for areas to tweak.

Strength of position

Kings or slave owners may have been able to force subjects to work, but a modern employer theoretically has to offer competitive terms and conditions to get someone to work, and people are theoretically free to sell their efforts, or not.

Then the theory becomes more complex and the playing field starts to tilt. People have to live, and they have to support their dependants. Not everyone is born with the intellectual gifts or social privileges that enable them to be entrepreneurs or high-earning professionals who can pick and choose their work and set their own prices. If someone can’t sell their efforts directly to a customer, they may have to accept whatever terms and conditions are available from a local employer or trader.

Location makes traders powerful

In fact, most people have to look and see what jobs there are locally and have to apply for one of them because they need the money, and can’t travel far, so they are in a very poor bargaining position. By contrast, capital providers and leaders and entrepreneurs and traders have always been in an excellent position to exploit this. In a town with high unemployment, or low wages, or indeed, throughout a poor country, potential employees will settle for the local wage rate for that kind of work, but that may differ hugely from the rate for similar work elsewhere.

The laws of supply and demand apply, but the locations of supply and demand need not be the same, and where they aren’t, traders are the ones who benefit, not those doing the work. Traders have existed and prospered for millennia and have often become very wealthy by exploiting the difference in labour costs and produce prices around the world.

Manufacturers can play the same geography game

Now with increasing globalisation, those with good logistics available to them can use these differences in manufacturing too, using cheap labour in one place to produce goods that can be sold for high prices in other places. Is it only the margins and the balance of bargaining power that determines whether this exploitation is fair or not, or is it also the availability of access to markets? What is a fair margin? How much of the profit should we allow traders or manufacturers to keep? If not enough, and markets are not free and lubricated enough, potential producers may stay idle and be even poorer because they can’t sell their efforts. If too much, someone else is getting rich at their expense.

Making access to free global markets easier and better will help

We need to create a system where people on both sides are empowered to ensure a fair deal. At the moment, it is tilted very heavily in favour of the trader, selling the product of cheap labour in expensive markets. When someone has no choice but to take what’s going, they are weak and vulnerable. If they can sell into a bigger market, they become stronger.

If everyone everywhere can see your produce and can get it delivered, then prices will tend to become fairer. There is still need for distributors, and they will still need paid, but distributors are just suppliers of a service in a competitive market too, and with a free choice of customer and supplier at every stage, all parties can negotiate to get a deal they are all content with, where no-one is at an a priori disadvantage.

It may still work out cheaper to buy from a great distance, but at least each party has agreed acceptable terms on a relatively level playing field. The web has already gone some way to improving market visibility but it is still difficult for many people to access the web with reasonable speed and security, and many more don’t understand how to do things like making websites, especially ones that have commerce functions.

If we can make better free access to markets, then unfair exploitation should become less of a problem, because it will be easier for people to sell their effort direct to an end customer, but it will have to become a lot easier to display your goods on the web for all to see without undue risk. Making the web easier to use and automating as much as possible of the security and administration should help a lot. This is happening quite quickly, but it needs time.

Import levies can reduce the incentive to exploit low wage workers

Levies can be added to imported goods so that someone can’t use cheap labour in one area to compete with the equivalent product made in the other. This is well tried and operates frequently where manufacturers pressure their governments to protect them from overseas competition that they see as unfair. However, it is usually aimed at protecting the richer employees from cheap competition rather than trying to increase wages for those being exploited in low wage economies. So it is far from ideal. Better a tool that allows pressure to increase the proportion of proceeds that go to the workers.

Peer pressure via transparency of margins

Another is to provide transparency in price attribution. If customers can see how much of the purchase price is going to each of the agents involved in its production and distribution chain, then pressure increases to pay a decent wage to the workers who actually make it, and less to those who merely sell it. Just like greed and caring, shame is another powerful emotion in the suite of human nature, and people will generally be more honest and fair if they know others can see what they are doing.

However, I do not expect this would work very well in practice, since most customers don’t care enough to get ethically involved in every purchase, and the further away and more socially distant the workers are, the less customers care. And if the person needing shamed is thousands of miles away, the peer pressure is non-existent. Yet again, location is important.

Transparency to the workforce

In economies across the developed world, typically about half of the profits of someone’s ‘job’ go to the person doing it and the other half goes to the owners of the company employing them. Transparency helps customers decide on supplier, but also helps employees to decide whether to work for a particular employer. They should of course be made fully aware of how they will be rewarded but also how much of their efforts will reward others. In a good company, the chiefs may be able to generate greater rewards for both staff and shareholders (and themselves), but as long as the details are all available, a free and informed choice can be made.

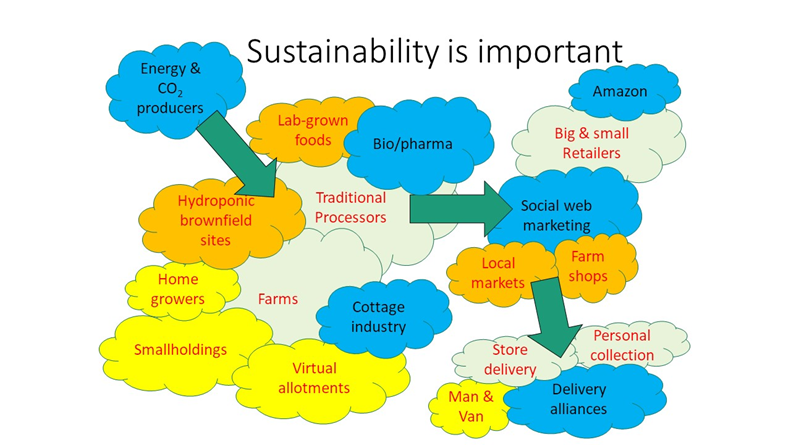

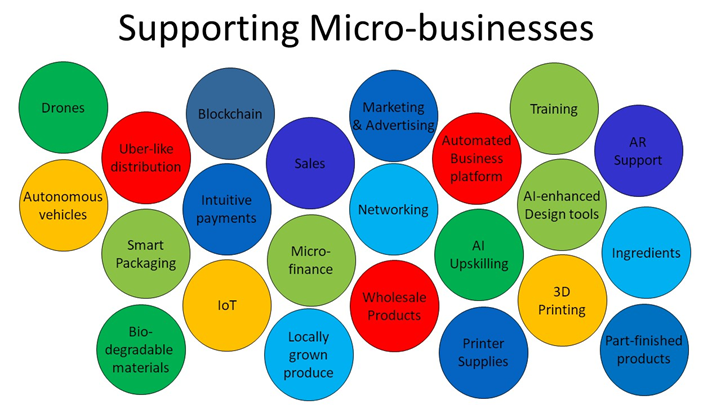

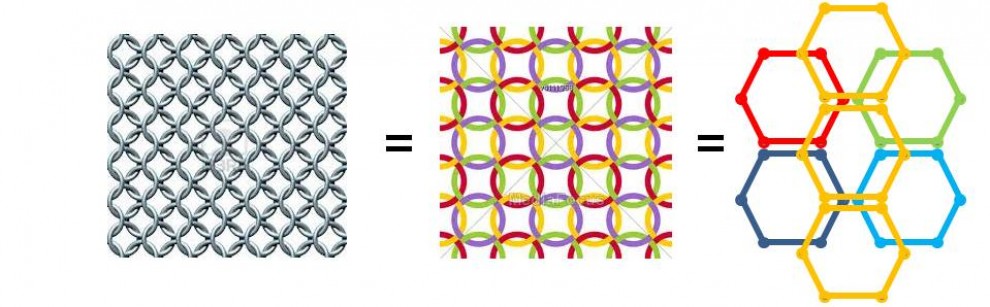

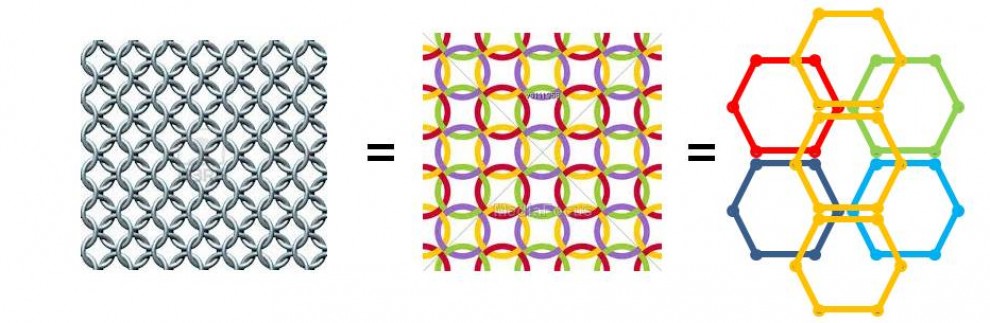

The community can generate its own businesses

In a well automated web environment, some company types would no longer be needed. Companies are often top down designs, with departments and employee structures that are populated by staff. The reverse is increasingly feasible, with groups of freelancers and small businesses using the web to find each other, and working loosely together as virtual companies to address the same markets the traditional company once did. But instead of giving half of the profits to a company owner, they reap the full rewards and share it between them. The administrative functions once done by the company are largely off-the-shelf and cheap. The few essential professional functions that the company provided can also be found as independents in the same marketplace. Virtual companies are the 21st century co-operative. The employees own the company and keep all the profits. Not surprisingly, many people have already left big companies to set up on their own as freelancers and small businesses.

Unfortunately, this model can’t work everywhere. Sometimes, a large factory or large capital investment is needed. This favours the rich and powerful and large companies, but there is again a new model that will start to come into play.

Investors don’t have to be wealthy individuals or big companies. They can also be communities. In a period where banks have become extremely unpopular, community banking will become very appealing once it is demonstrated to work. Building societies will make a comeback, but even they are more organised than is strictly necessary in a mature web age.

Linking people in a community with some savings to others who need to borrow it to make a business will become easier as social and business networking develops the trust based communities needed to make this feasible. Trust is essential, but it is often based on social knowledge, and recommendations can be shared. Abusers could be filtered out, and in any case, their potential existence creates a sub market for risk assessors and insurance specialists, who may have left companies to go freelance too. Communities may provide their own finance for companies that provide goods and services for the local community. This is a natural development of the routine output of today’s social entrepreneurs. Community based company creation, nurturing, staffing and running is a very viable local model that could work very well for many areas of manufacturing, services, food production and community work. Some of this is already embryonic on the net today as crowd-funding, but it could grow nicely as the web continues to mature.

Whether this could grow to the size needed to make a car factory or a chip fabrication plant or a major pharmaceutical R&D lab is doubtful, but even these models are being challenged – future cars may not need the same sorts of production, a lot of biotech is suited to garden sheds, and local 3D printing can address a lot of production needs, even some electronic ones. So the number of industries completely immune to this trend is probably quite small. Most will be affected a bit or greatly. Companies that are deeply woven into communities may dominate the future commercial landscape. And as that happens, the willingness and the capability to exploit others reduces.

If we move towards this kind of system, companies will be more responsive to our needs, while providing a stronger base on which to build other enterprises. Integrated into community banking, it is hard to see why we would need today’s banks in such a world. We could dispense with a huge drain on our finances. Banks contribute no extra to the overall economy (taken globally) and siphon off considerable fees. Without them, people could keep more of what they earn and growth would accelerate.

Exploitation via celebrity?

In the UK, we don’t get very good value for money from our footballers. They get enormously generous pay for often poor performance. Individually, few of them seem to be intellectual giants, but the industry as a whole has grown enormously. By creating a monopoly of well supported clubs, they have established a position where they can extract huge fees for tickets, merchandising and TV coverage. The ordinary person has to pay heavily to watch a match, while the few people putting on the show get enormous rewards. This might look like exploitation at first glance, but is it?

It is certainly shrewd business dealing by the football industry, but mainly, the TV companies seem to be stupid negotiators. If they declined to pay huge fees to air the matches, the most likely outcome is that fees would tumble to a very nominal level quickly, after which the football associations would have to start paying the TV channels for air time to sell the game coverage direct to fans, or else distribute coverage via the net. They would have no choice. TV companies could easily end up being paid to show matches. When viewers each have to pay explicitly to watch rather than have the fees hidden in a TV license or satellite subscription, the takings would drop and the wages given to footballers would inevitably follow. However, they would still be paid very well, probably still grossly overpaid. We may still moan at them, but they would then simply be benefiting from scale of market, not exploiting. If you can sell unique entertainment or indeed any other valuable service to a large number of people you can generate a lot of income. If you don’t need many staff, they can be paid very well. Individual celebrities have emerged from every area of entertainment who get huge incomes simply because they can generate small amounts of cash from very large numbers of people. If many individuals vale the product highly, as in top level boxing for example, stars can be massively rewarded.

It is hard to label this as exploitation though. It is simply taking advantage of scale. If I can sell something at a sensible price and make a decent income from a small number of customers, someone better who can sell an even better product at the same price to a much larger number of people will be paid far more. In this case, the customer gets a better product for the same outlay, so is hardly being exploited, but the superior provider will get richer. If we forced them to sell better products cheaper than someone else’s inferior one, simply to reduce their income, we would destroy the incentive to be good. No-one benefits from that.

Entertainment isn’t unique here. The same goes for writing a good game or a piece or app, or inventing Facebook. In fact, the basis of the information economy, which includes entertainment, is very different from the industrial one. Information products can be reproduced, essentially without cost without losing their value. There are lots of products that can be sold to lots of people for low prices that do no harm to anyone, add quality to lives and still make providers very wealthy. Let’s hope we can find some more.

So even without exploitation, we will still have the super-rich

There will always be relatively poor and super rich people. But I think that is OK. What we should try to ensure is that people don’t get rich by abusing or exploiting others. If they can still get rich without exploiting anyone, then at least it is fair, and they should enjoy their wealth, within the law, provided that the law prevents them from using it to abuse or exploit others. Let’s not punish wealth per se, but focus instead on how it has been obtained, and on eliminating abuses.

In any case, there is a natural limit to how much you can use

As the global population climbs, and people get wealthier everywhere, the number of super-rich will grow, even if we eliminate unfairness and exploitation totally. But if we take huge amounts of money out of the system and put it in someone’s bank account, they will not be able to dispose of it all. In most cases, without great determination and extravagance indeed, the actual practical loading that an individual can make on the system is quite limited. They can only eat so much, occupy so much land, use up so much natural resource, have so many lovers. The rest of the world’s resources, of whatever kind, are still available to everyone else. So their reward is naturally capped, they simply don’t have the time or energy to use up any more. Any money they put in investments or cash is just a figure on a spreadsheet, and a license to use the power it comes with.

But while power is important in other ways, it is not directly an economic drain – it doesn’t affect how much is left for the rest of us. Above a certain amount that varies with individual imagination, taste and personality, extra wealth doesn’t give anything except power. It effectively disappears, and supply and demand and prices balance for the rest accordingly.

Power takes us full circle

When we have spent all we can, and just get extra power from the extra income, it is time to start asking other kinds of questions. Some would challenge the right of the super-rich to use their wealth to do things that others might think should be decided by the whole population. Should rich people be allowed to use their wealth to tackle Aids in Africa, run their own space programs, or build influential media empires? Well, we can make laws to prevent abuses and exploitation. We can employ the principle of ‘To each according to their effort’. Once we’ve done that, I don’t see how or why we should try to stop rich people doing what they want within the law.

Was the Roman villa I visited built by well rewarded workers? Probably not. Could something equivalent be built by a rich person who has done no harm to anyone, or even brought universal good? Yes. It isn’t what they build or how much they earn that matters, but how they earned it. Money earned via exploitation is very different from money earned by effort and talent.

In future, I will have to read up on the owners of stately homes before I get angry at them. And we must certainly consider these issues as we build our sustainable capitalism in the future.

Stupidity

You might think that the people at the top would be the smartest, but unfortunately, they usually aren’t. Some studies have shown that CEOs have an average IQ of around 130, which is fairly good but nothing special, and many of the staff below them would generally be smarter. That means that whatever skills might have got them there, their overall understanding of the world is limited and the quality of their decisions is therefore also limited. Considering that, we often pay board members far more than is necessary and we often put stupid people in charge. This is not a good combination, and it ultimately undermines the workings of the whole economy. I’ll look at stupidity in more detail later.

With corruption, exploitation, loose values, no real incentives to behave well, and sheer stupidity all fighting against capitalism as we have it today, it is a miracle it works at all, but it does and that argues for its fundamental strength. If we address these existing problems and start to protect against the coming ones, we will be fine, maybe even better than fine. We’d be flying.

There are some new problems coming too, and sometimes major trends can conceal less conspicuous ones, but sometimes these less conspicuous trends can build over time into enormous effects. Global financial turmoil and re-levelling due to development are largely concealing another major trend towards automation, a really key problem in the future of capitalism. If we look at the consequences of developing technology, we can see an increasingly automated world as we head towards the far future. Most mechanical or mental jobs can be automated eventually, leaving those that rely on human emotional and interpersonal skills, but even these could eventually be largely automated. That would obviously have a huge effect on the nature of our economies. It is good to automate; it adds the work of machines to that of humans, but if you get to a point where there is no work available for the humans to take, then that doesn’t work so well. Overall effectiveness is reduced because you still have to finance the person you replaced somehow. We are reaching that point in some areas and industries now.

One idea that has started to gain ground is that of reducing the working week. It has some merit. If there is enough work for 50 hours a week, maybe it is better to have 2 people working 25 each than one working 50 and one unemployed, one rich and one poor. If more work becomes available, then they can both work longer again. This becomes more attractive still as automation brings the costs down so that the 25 hours provides enough to live well. It is one idea, and I am confident there will be more.

However, I think there is another area we ought to look for a better solution – re-evaluating ownership.

Sometimes taking an extreme example is the best way to illustrate a point. In an ultra-automated pure capitalist world, a single person (or indeed even an AI) could set up a company and employ only AI or robotic staff and keep all the proceeds. Wealth would concentrate more and more with the people starting with it. There may not be any other employment, given that almost anything could be automated, so no-one else except other company owners would have any income source. If no-one else could afford to buy the products, their companies would die, and the economy couldn’t survive. This simplistic example nevertheless illustrates that pure capitalism isn’t sustainable in a truly high technology world. There would need to be some tweaking to distribute wealth effectively and make money go round a bit. Much more than current welfare state takes care of.

Perhaps we are already well on the way. Web developments that highly automate retailing have displaced many jobs and the same is true across many industries. Some of the business giants have few employees. There is no certainty that new technologies will create enough new jobs to replace the ones they displace.

We know from abundant evidence that communism doesn’t work, so if capitalism won’t work much longer either, then we have some thinking to do. I believe that the free market is often the best way to accomplish things, but it doesn’t always deliver, and perhaps it can’t this time, and perhaps we shouldn’t just wait until entire industries have been eradicated before we start to ask which direction it should go.

Culture tax – Renting shared infrastructure, culture and knowledge

The key to stopping the economy grinding to a halt due to extreme wealth concentration may lie in the value of accumulated human knowledge. Apart from short-term IP such as patents and copyright, the whole of humanity collectively owns the vast intellectual wealth accumulated via the efforts of thousands of generations. Yettraditionally, when a company is set up, no payment is made for the use of this intellectual property; it is assumed to be free. The effort and creativity of the founders, and the finance they provide, are assumed to be the full value, so they get control of the wealth generated (apart from taxes).

Automated companies make use of this vast accumulated intellectual wealth when they deploy their automated systems. Why should ownership of a relatively small amount of capital and effort give the right to harness huge amounts of publicly owned intellectual wealth without any payment to the other owners, the rest of the people? Why should the rest of humanity not share in the use of their intellectual property to generate reward? This is where the rethinking should be focused. There is nothing wrong with people benefiting from their efforts, making profit, owning stuff, controlling it, but it surely is right that they should make proper payment for the value of the shared intellectual property they use. With properly shared wealth generation, everyone would have income, and the system might work fine.

Ownership is the key to fair wealth distribution in an age of accelerating machine power. The world economy has changed dramatically over the last two decades, but we still think of ownership in much the same ways. This is where the biggest changes need to be made to make capitalism sustainable. At the moment, of all the things needed to make a business profitable, capital investment is given far too great a share of control and of the output. There are many other hugely important inputs that are not so much hidden as simply ignored. We have become so used to thinking of the financial investors owning the company that we don’t even see the others. So let me remind you of some of the things that the investors currently get given to them for free. I’ll start with the blindingly obvious and go on from there.

First and most invisible of all is the right to do business and to keep the profits. In some countries this isn’t a right, but in the developed world we don’t even think of it normally.

The law, protecting the company from having all its stuff stolen, its staff murdered, or its buildings burned down.

The full legal framework, all the rules and regulations that allow the business to trade on known terms, and to agree contracts with the full backing of the law.

Ditto the political framework.

Workforce education – having staff that can read and write, and some with far higher level of education

Infrastructure – all the roads, electricity, water, gas and so on. Companies pay for ongoing costs, maintenance and ongoing development, but pay nothing towards the accumulated historical establishment of these.

Accumulated public intellectual property. It isn’t just access to infrastructure they get free, it is the invention of electricity, of plumbing, of water purification and sewage disposal techniques, and so on.

Human knowledge, science, technology knowhow. We all have access to these, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that there should be an automatic right for anyone to use them without due compensation to the rest of the community. We assume that as a right, but it wasn’t really ever explicitly agreed, ever. It has just evolved. If someone invents something and patents it, we assume they have every right to profit from it. If they use an invention in common ownership, such as the wheel, why should they not pay the rest of society for the right to use it for personal commercial gain?

Think of it another way. If a village has a common, everyone has the right to let their animals feed off the grass. That works fine when there are only a few animals, but if everyone has a large herd, it soon breaks down. The common might be taken under local council control, and rented out, returning due value to the community. So it could be for all other commonly held knowledge. And there is a lot of it, thousands of years’ worth.

Culture is also taken for granted, including hand-me-down business culture, all the stuff that makes up an MBA, or even everyday knowledge about how businesses operate or are structured. So are language, and social structure that ensures that all the other supporting roles in society are somehow provided. We may take these for granted because they belong to us all, but they are a high value asset and if someone gains financially from using them, why should they not pay some of the profits to the rest of the owners as they would for using any other asset?

So the question is: should business pay for it, as it pays for capital and labour?

This all adds up to an enormous wealth of investment by thousands of generations of people. It is shared wealth but wealth nonetheless. When a company springs up now, it can access it all, take it all for granted, but that doesn’t mean it is without value. It is immensely valuable. So perhaps it is not unreasonable to equate it in importance to the provision of effort or finance. In that case, entrepreneurs should pay back some of their gains to the community.

Reward is essential, but fair’s fair

A business will not happen unless someone starts it, works hard at setting it up, getting it going, with all the stress and sacrifice that often needs. They need to be assured of a decent reward or they won’t bother. The same goes for capital providers, if they are needed. They also want something to show for the risk they have taken. Without enough incentive, it won’t work, and that should always be retained in our thinking when we redesign. But it is also right to look at the parallel investment by the community in terms of all the things listed above. That should also be rewarded.

This already happens to some degree when companies and shareholders pay their taxes. They contribute to the ongoing functioning of the society and to the development to be handed on to the next generation, just as individuals do. But they don’t explicitly pay any purchase price or rent for the social wealth they assumed when they started. The host community needs to be better and more explicitly integrated into the value distribution of a company in much the same way as shareholders or a board.

The amount that should be paid is endlessly debatable, and views would certainly differ between parties, but it does offer a way of tweaking capitalism that ensures that businesses develop and use new technology in such a way that it can be sustained. We want progress, but if all jobs were to be replaced by a smart machines, then we may have an amazingly efficient system, but if nobody has a job, and everyone is on low-level welfare, then nobody can afford to buy any of the products so it would seize up. Conventional taxes might not be enough to sustain it all. On the other hand, linking the level of payments from a company to the social capital they use when they deploy a new machine means that if they make lots of workers redundant by automation, and there are no new jobs for them to go to, then a greater payment would be incurred. While business overall is socially sustainable and ensures reasonably full employment, then the payments can remain zero or very low.

But we have the makings of an evolution path that allows for fair balancing of the needs of society and business.

The assignment of due financial value to social wealth and accumulated knowledge and culture ensures that there is a mechanism where money is returned to the society and not just the mill owner. With payment of the ‘social dividend’, government and ultimately people can then buy the goods. The owner should still be able to get wealthy, but the system is still able to work because the money can go around. But it also allows linking the payments from a business to the social sustainability of its employment practices. If a machine exists that can automate a job, it has only done so by the accumulated works of the society, so society should have some say in the use of that machine and a share of the rewards coming from it.

So we need to design the system, the rules and conditions, so that people are aware when they set up a business of the costs they will incur, under what conditions. They would also know that if they change their employment via automation, then the payments for the assumed knowledge in the machines and systems will compensate for the social damage that is done by the redundancy if no replacement job exists. The design will be difficult, but at least there is a potential basis for the rules and equations and while we’re looking at automation, we can use the same logic to address the other ethical issues surrounding business, such as corruption and exploitation, and factor those into our rules and penalties too.

There remains the question of distribution of the wealth from this social dividend. It could be divided equally of course, but more likely, since political parties would have their priority lists, it would have some sort of non-equal distribution. That is a matter for politicians.

Summarising, there are many problems holding business and society back today and standing in the way of sustainable capitalism. Addressing them will make us all better off. Some of them can be addressed by a similar mechanism to that which I recommend for balancing automation against social interests. Automation is good, wealth is good, and getting rich is good. We should not replace capitalism because it mostly works, but it is now badly in need of a system update and some maintenance work. When we’ve done all that, we will have a capitalist system that rewards effort and wealth provision just as today, but also factors in the wider interests – and investment – of the whole community. We’ll all benefit, and it will be sustainable.

Sustainable tax and welfare

Tax systems seem to have many loopholes that stimulate jobs in creative accountancy, but deprive nations of tax. Sharp cut-offs instead of smooth gradients create problems for people whose income rises slightly above thresholds. We need taxation, but it needs to be fair and transparent, and what that means depends on your political allegiances, but there is some common ground. Most of us would prefer a simpler system than the ludicrously complicated one we have now and most of us would like a system that applies to everyone and avoids loopholes.

The rich are becoming ever richer, even during the economic problems. In fact some executives on bonus structures linked to short-term profits appear to be using the recession as an excuse to depress wages to increase company profits and thereby be rewarded more themselves. Some rich people pay full tax, some avoid paying taxes by roaming around the world, never staying anywhere long enough to incur local tax demands. It may be too hard to introduce global taxes, or to stop tax havens from operating, but it is possible to ensure that all income earned from sales in a country is taxed here.

Electronic cash opens the potential for ensuring that all financial transactions in the country go through a tax gateway, which could immediately and at the point of transaction determine what tax is due and deduct it. If we want, a complex algorithm could be used, taking into account the circumstances of the agencies involved and the nature of the transaction – number crunching is very cheap and no human needs to be involved after the algorithms are determined so it could be virtually cost-free however complex. Or we could decide that the rate is a fixed percentage regardless of purpose. It doesn’t even have to threaten privacy, it could be totally anonymous if there are no different rates. With all transactions included, and the algorithms applying at point of transaction, there would be no need to know or remember who is involved or why.

Different sorts of income sources are taxed differently today. It makes sense to me to have a single flat tax of rate for all income, whatever its source – why should it matter how you get your income, surely the only thing that matters is how much you get? Today, there are many rates and exceptions. Since people can take income by pay, dividends, capital gains, interest, gambling, lottery wins, and inheritance, a fair system would just count it all up and tax it all at the same rate. This could apply to companies too, at the same rate; since some people own companies and money accumulating in them is part of their income. Ditto property development, any gains when selling or renting a property could be taxed at that rate. Company owners would be treated like everyone else, and pay on the same basis as employees.

I believe flat taxes are a good idea. They have been shown to work well in some countries, and can stimulate economic development. If there are no exceptions, if everyone must pay a fixed percentage of everything they get, then the rich still pay more tax, but are better incentivised to earn even more. Accountants wouldn’t be able to prevent rich people avoiding tax just by laundering it via different routes or by relabelling it.

International experience suggests that a flat tax rate of around 20% would probably work. So, you’d pay 20% on everything you earn or your company earns, or you inherit, or win, or are given or whatever. Some countries also tax capital, encouraging people to spend it rather than hoard, but this is an optional extra. There is something quite appealing about a single rate of tax that applies to everyone and every institution for every transaction. It is simpler, with fewer opportunities to abdicate responsibility to pay, and any income earned in the country would be taxed in the country.

There are a few obvious problems that need solved. Husbands and wives would not be able to transfer money between them tax-free, nor parents giving their kids pocket money, so perhaps we need to allow anyone tax-free interchange with their immediate family, as determine by birth, marriage or civil partnership. When people buy a new house, or change their share portfolio, perhaps it should just be on the value difference that the 20% would apply. So a few tweaks here and there would be needed, but the simpler and the fewer exceptions we introduce, the better.

So what about poorer people, how will they manage? The welfare system could be similarly simplified too. We can provide simply for those that need help by giving a base allowance to every adult, regardless of need, set so that if that is your only income, it would be sufficient to live modestly but in a dignified manner. Any money earned on top of that ensures that there is an incentive to work, and you won’t become poorer by earning a few pounds more and crossing some threshold.

(Since I first blogged about this in Jan 2012, the Swiss have agreed a referendum (in Oct 2013) on what they call the Citizen Wage Initiative, which is exactly this same idea. I guess it has been around in various forms for ages, but if the Swiss decide to go ahead with it, it might soon be real. At a modest level of payment, it is workable now, the main issue being that there still needs to be a big enough incentive for people to work, or many won’t, and the economy would dive. The Swiss are considering a wage of 2000 Francs per month, which might be too generous, as it would allow a household with a few adults to live fairly comfortably without working. Having noted that, I still think the idea itself is very sound, the level just needs to be carefully set to preserve the work incentive.)

There is also no need to have a zero tax threshold. People who earn enough not to need welfare would be paying tax according to their total income anyway, so it all sorts itself out. With everyone getting the same allowance, admin costs would be very low and since admin costs currently waste around a third of the money, this frees up enough money to make the basic allowance 50% more generous. So everyone benefits.

Children could also be provided with an allowance, which would go to their registered parent or guardian just as today in lieu of child benefits. Again, since all income is taxed at the same rate regardless of source, there is no need to means test it. There should be as few other benefits as possible. They shouldn’t be necessary if the tax and allowance rate is tuned correctly anyway. Those with specific needs, such as some disabled people, could be given what they need rather than a cash benefit, so that there is less incentive to cheat the system.

Such a system would reduce polarisation greatly. The extremes at the bottom would be guaranteed a decent income, while those at the top would be forced to pay their proper share of taxes, however they got their wealth. If they still manage to be rich, then their wealth will at least be fair. It also guarantees that everyone is better off if they work, and that no-one falls through the safety net.

If everyone gets the allowance, the flat tax rate would mean that anyone below average earnings would hardly pay any income tax, any work that someone on benefits undertakes would result in a higher standard of living for them, and those on much more will pay lots. The figures look generous, but company income and prices will adjust too, and that will also rebalance it a bit. It certainly needs tuned, but it could work.

In business, the flat tax applies to all transactions, and where there is some sort of swap, such as property or shares, then the tax could be on the value difference. So, in shops, direct debits, or internet purchases, the tax would be a bit higher than the VAT rate today, and other services would also attract the same rate. With no tax deductions or complex VAT rules, admin is easier but more things are taxed. This makes it harder for companies to avoid tax by being based overseas and that increased tax take directly from income to companies means that the tax needed from other routes falls. Then, with a re-balanced economy, and everyone paying on everything, the flat rate can be adjusted until the total national take is whatever is agreed by government.

This just has to be simpler, fairer, and less wasteful and a better stimulus for hard work than the messy and unfair system we have now, full of opportunities to opt out at the top if you have a clever accountant and disincentives to work at the bottom.

The economy today is big enough to provide basic standard of living to everyone, but thanks to economic growth it will be possible to have a flat tax and a basic welfare payment equivalent to today’s average income within 45 years. If those who want economic growth to stop get their way, the poor will be condemned to at best a basic existence.

Linking tax and welfare to social networks

We often hear the phrase ‘care in the community’. Nationalisation of social care has displaced traditional care by family and local community to some degree. Long ago, people who needed to be looked after were looked after by those who are related or socially close, either by geography or association. It could be again, and may even be necessary as care rationing is a strong likelihood. Meanwhile, wealth is being redefined in many countries now, with high quality social relationships becoming recognised as valuable and a major contributor to overall quality of life.

Social care costs money, and will inevitably be rationed as the population ages, so why not link it back to social structure as it used to be? In much the same way that financial welfare is only available to those that need it, those with social wealth could and perhaps should be cared for by those who love them instead of by the state. They would likely be happier, and it would cost less. Those that have low connectedness, i.e. few friends and family, should then be the rightful focus of state care. Everyone could be cared for better and the costs would be more manageable.

We already know people’s social connectedness very well, it is indicated by many easily measurable factors, and every year it gets easier. The numbers and strength of contacts on social networking sites is one clue, so is email and messaging use, so is phone use. Geographic proximity can be determined by information in the electoral roll. So it is possible to determine algorithms based on these many various factors that would determine who needs care from the state and who should be able to get it from social contacts.

Many people wouldn’t like that, resenting being forced to care for other people, so how can we make sure people do take care of those they are ‘allocated’ to? Well, that could be done by linking taxation to the care system in such a way that the amount of care you should be providing would be determined by your social connectivity, and providing that care yields tax discount. Or you could just pay your full quota of taxes and abdicate provision to the state. But by providing a high valuation on actual care, it would encourage people to choose to provide care rather than to pay the tax.

Social wealth could thus be linked to social tax, and this social tax could be paid either as care or cash. The technology of social networking has given us the future means to link the social care side of social security into social connectedness. Those who are socially poor would receive the greatest focus of state provision and those who gain most socially from their lives would have to put more in too. We do that with money, why not also with social value? It sounds fair to me.