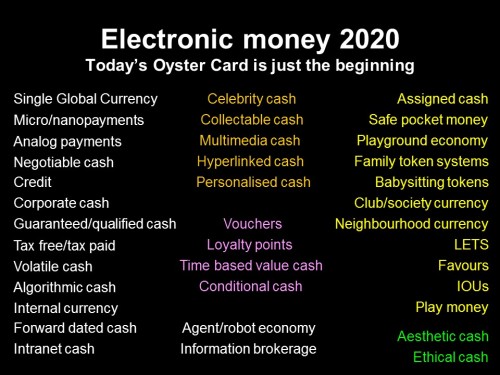

Picture first, I’m told people like to see pics in blogs. This one is from 1998; only the title has changed since.

Every once in a while I have to go to a bank. This time it was my 5th attempt to pay off a chunk of my Santander Mortgage. I didn’t know all the account details for web transfer so went to the Santander branch. Fail – they only take cash and cheques. Cash and what??? So I tried via internet banking. Entire transaction details plus security entered, THEN Fail – I exceeded what Barclays allows for their fast transfers. Tried again with smaller amount and again all details and all security. Fail again, Santander can’t receive said transfers, try CHAPS. Tried CHAPS, said it was all fine, all hunkydory. Happy bunny. Double fail. It failed due to amount exceeding limit AND told me it had succeeded when it hadn’t. I then drove 12 miles to my Barclays branch who eventually managed to do it, I think (though I haven’t checked that it worked yet).

It is 2015. Why the hell is it so hard for two world class banks to offer a service we should have been able to take for granted 20 years ago?

Today, I got tweeted about Ripple Labs and a nice blog that quote their founder sympathising with my experience above and trying to solve it, with some success:

http://www.wfs.org/blogs/richard-samson/supermoney-new-wealth-beyond-banks-and-bitcoin

Ripple seems good as far as it goes, which is summarised in the blog, but do read the full original:

Basically the Ripple protocol “provides the ability for humans to confirm financial transactions without a central operator,” says Larsen. “This is major.” Bitcoin was the first technology to successfully bypass banks and other authorities as transaction validators, he points out, “but our method is much cheaper and takes only seconds rather than minutes.” And that’s just for starters. For example, “It also leverages the enormous power of banks and other financial institutions.”

The power of the value web stems from replacing archaic back-end systems with all their cumbersome delays and unnecessary costs.

That’s great, I wish them the best of success. It is always nice to see new systems that are more efficient than the old ones, but the idea is early 1990s. Lots of IT people looked at phone billing systems and realised they managed to do for a penny what banks did for 65 pennies at the time, and telco business cases were developed to replace the banks with pretty much what Ripple tries to do. Those were never developed for a variety of reasons, both business and regulatory, but the ideas were certainly understood and developed broadly at engineer level to include not only traditional cash forms but many that didn’t exist then and still don’t. Even Ripple can only process transactions that are equivalent to money such as traditional currencies, electronic cash forms like bitcoin, sea shells or air-miles.

That much is easy, but some forms require other tokens to have value, such as personalized tokens. Some value varies according to queue lengths, time of day, who is spending it to whom. Some needs to be assignable, so you can give money that can only be used to purchase certain things, and may have a whole basket of conditions attached. Money is also only one form of value, and many forms of value are volatile, only existing at certain times and places in certain conditions for certain transactors. Aesthetic cash? Play money? IOUs? Favours?These are all a bit like cash but not necessarily tradable or exchangeable using simple digital transaction engines because they carry emotional weighting as well as financial value. In the care economy, which is now thankfully starting to develop and is finally reaching concept critical mass, emotional value will become immensely important and it will have some tradable forms, though much will not be tradable ever. We understood all that then, but are still awaiting proper implementation. Most new startups on the web are old ideas finally being implemented and Ripple is only a very partial implementation so far.

Here is one of my early blogs from 1998, using ideas we’d developed several years earlier that were no longer commercially sensitive – you’ll observe just how much banks have under-performed against what we expected of them, and what was entirely feasible using already known technology then:

Future of Money

ID Pearson, BT Labs, June 98

Already, people are buying things across the internet. Mostly, they hand over a credit card number, but some transactions already use electronic cash. The transactions are secure so the cash doesn’t go astray or disappear, nor can it easily be forged. In due course, using such cash will become an everyday occurrence for us all.

Also already, electronic cash based on smart cards has been trialled and found to work well. The BT form is called Mondex, but it is only one among several. These smart cards allow owners to ‘load’ the card with small amounts of money for use in transactions where small change would normally be used, paying bus fares, buying sweets etc. The cards are equivalent to a purse. But they can and eventually will allow much more. Of course, electronic cash doesn’t have to be held on a card. It can equally well be ‘stored’ in the network. Transactions then just require secure messaging across the network. Currently, the cost of this messaging makes it uneconomic for small transactions that the cards are aimed at, but in due course, this will become the more attractive option, especially since you no longer lose your cash when you lose the card.

When cash is digitised, it loses some of the restrictions of physical cash. Imagine a child has a cash card. Her parents can give her pocket money, dinner money, clothing allowance and so on. They can all be labelled separately, so that she can’t spend all her dinner money on chocolate. Electronic shopping can of course provide the information needed to enable the cash. She may have restrictions about how much of her pocket money she may spend on various items too. There is no reason why children couldn’t implement their own economies too, swapping tokens and IOUs. Of course, in the adult world this grows up into local exchange trading systems (LETS), where people exchange tokens too, a glorified babysitting circle. But these LETS don’t have to be just local, wider circles could be set up, even globally, to allow people to exchange services or information with each other.

Electronic cash can be versatile enough to allow for negotiable cash too. Credit may be exchanged just as cash and cash may be labelled with source. For instance, we may see celebrity cash, signed by the celebrity, worth more because they have used it. Cash may be labelled as tax paid, so those donations from cards to charities could automatically expand with the recovered tax. Alternatively, VAT could be recovered at point of sale.

With these advanced facilities, it becomes obvious that the cash needs to become better woven into taxation systems, as well as auditing and accounting systems. These functions can be much more streamlined as a result, with less human administration associated with money.

When ID verification is added to the transactions, we can guarantee who it is carrying out the transaction. We can then implement personal taxation, with people paying different amounts for the same goods. This would only work for certain types of purchase – for physical goods there would otherwise be a thriving black market.

But one of the best advantages of making cash digital is the seamlessness of international purchases. Even without common official currency, the electronic cash systems will become de facto international standards. This will reduce the currency exchange tax we currently pay to the banks every time we travel to a different country, which can add up to as much as 25% for an overnight visit. This is one of the justifications often cited for European monetary union, but it is happening anyway in global e-commerce.

Future of banks

Banks will have to change dramatically from today’s traditional institutions if they want to survive in the networked world. They are currently introducing internet banking to try to keep customers, but the move to digital electronic cash, held perhaps by the customer or an independent third party, will mean that the cash can be quite separate from the transaction agent. Cash does not need to be stored in a bank if records in secured databases anywhere can be digitally signed and authenticated. The customer may hold it on his own computer, or in a cyberspace vault elsewhere. With digital signatures and high network security, advanced software will put the customer firmly in control with access to any facility or service anywhere.

In fact, no-one need hold cash at all, or even move it around. Cash is just bits today, already electronic records. In the future, it will be an increasingly blurred entity, mixing credit, reputation, information, and simply promises into exchangeable tokens. My salary may be just a digitally signed certificate from BT yielding control of a certain amount of credit, just another signature on a long list as the credit migrates round the economy. The ‘promise to pay the bearer’ just becomes a complex series of serial promises. Nothing particularly new here, just more of what we already have. Any corporation or reputable individual may easily capture the bank’s role of keeping track of the credit. It is just one service among many that may leave the bank.

As the world becomes increasingly networked, the customer could thus retain complete control of the cash and its use, and could buy banking services on a transaction by transaction basis. For instance, I could employ one company to hold my cash securely and prevent its loss or forgery, while renting the cash out to companies that want to borrow via another company, keeping the bulk of the revenue for myself. Another company might manage my account, arrange transfers etc, and deal with the taxation, auditing etc. I could probably get these done on my personal computer, but why have a dog and bark yourself.

The key is flexibility, none of these services need be fixed any more. Banks will not compete on overall package, but on every aspect of service. Worse still (for the banks), some of their competitors will be just freeware agents. The whole of the finance industry will fragment. The banks that survive will almost by definition be very adaptable. Services will continue and be added to, but not by the rigid structures of today. Surviving banks should be able to compete for a share of the future market as well as anyone. They certainly have a head start in many of the required skills, and have the advantage of customer lethargy when it comes to changing to potentially better suppliers. Many of their customers will still value tradition and will not wish to use the better and cheaper facilities available on the network. So as always, it looks like there will be a balance.

Firstly, with large numbers of customers moving to the network for their banking services, banks must either cater for this market or become a niche operator, perhaps specialising in tradition, human service and even nostalgia. Most banks however will adapt well to network existence and will either be entirely network based, or maintain a high street presence to complement their network presence.

High Street banking

Facilities in high street banking will echo this real world/cyberspace nature. It must be possible to access network facilities from within the banks, probably including those of competitors. The high street bank may therefore be more like shops today, selling wares from many suppliers, but with a strongly placed own brand. There is of course a niche for banks with no services of their own at all who just provide access to services from other suppliers. All they offer in addition is a convenient and pleasant place to access them, with some human assistance as appropriate.

Traditional service may sometimes be pushed as a differentiator, and human service is bound to attract many customers too. In an increasingly machine dominated world, actually having the right kind of real people may be significant value add.

But many banks will be bursting with high technology either alongside or in place of people. Video terminals to access remote services, perhaps with translation to access foreign services. Biometric identification based on iris scan, fingerprints etc may be used to authenticate smart cards, passports or other legal documents before their use, or simply a means of registering securely onto the network. High quality printers and electronic security embedding would enable banks to offer additional facilities like personal bank notes, usable as cash.

Of course, banks can compete in any financial service. Because the management of financial affairs gives them a good picture of many customer’s habits and preferences, they will be able to use this information to sell customer lists, identify market niches for new businesses, and predict the likely success of customers proposing setting up businesses.

As they try to stretch their brands into new territories, one area they may be successful is in information banking. People may use banks as the publishers of the future. Already knowledge guilds are emerging. Ultimately, any piece of information from any source can be marketed at very low publishing and distribution cost, making previously unpublishable works viable. Many people have wanted to write, but have been unable to find publishers due to the high cost of getting to market in paper. A work may be sold on the network for just pennies, and achieve market success by selling many more copies than could have been achieved by the high priced paper alternative. The success of electronic encyclopedias and the demise of Encyclopedia Britannica is evidence of this. Banks could allow people to upload information onto the net, which they would then manage the resultant financial transactions. If there aren’t very many, the maximum loss to the bank is very small. Of course, electronic cash and micropayment technology mean that the bank is not necessary, but for many, it may smooth the road.

Virtual business centres

Their exposure to the detailed financial affairs of the community put banks in a privileged position in identifying potential markets. They could therefore act as co-ordinators for virtual companies and co-operatives. Building on the knowledge guilds, they could broker the skills of their many customers to existing virtual companies and link people together to address business needs not addressed by existing companies, or where existing companies are inadequate or inefficient. In this way, short-term contractors, who may dominate the employment community, can be efficiently utilised to everyone’s gain. The employees win by getting more lucrative work, their customers get more efficient services at lower cost, and the banks laugh to themselves.

Future of the stock market

In the next 10 years, we will probably see a factor of 1000 in computer speed and memory capacity. In parallel with hardware development, there are numerous research forays into software techniques that might yield more factors of 10 in the execution speed for programs. Tasks that used to take a second will be reduced to a millisecond. As if this impact were not enough, software will very soon be able to make logical deductions from the flood of information on the internet, not just from Reuters or Bloomberg, but from anywhere. They will be able to assess the quality and integrity of the data, correlate it with other data, run models, and infer likely other events and make buy or sell recommendations. Much dealing will still be done automatically subject to human-imposed restrictions, and the speed and quality of this dealing could far exceed current capability.

Which brings problems…

Firstly, the speed of light is fast but finite. With these huge processing speeds, computers will be able to make decisions within microseconds of receiving information. Differences in distance from the information source become increasingly important. Being just 200m closer to the Bank of England makes one microsecond difference to the time of arrival of information on interest rates, the information, insignificant to a human, but of sufficient duration for a fast computer to but or sell before competitors even receive the information. As speeds increase further over following years, the significant distance drops. This effect will cause great unfairness according to geographic proximity to important sources. There are two obvious outcomes. Either there becomes a strong premium on being closest, with rises in property values nearby to key sources, or perhaps network operators could be asked to provide guaranteed simultaneous delivery of information. This is entirely technically feasible but would need regulation, otherwise users could simply use alternative networks.

Secondly, exactly simultaneous processing will cause problems. If many requests for transactions arrive at exactly the same moment, computers or networks have to give priority in some way. This is bound to be a source of contention. Also, simultaneous events can often cause malfunctions, as was demonstrated perfectly at the launch of Big Bang. Information waves caused by such events are a network phenomenon that could potentially crash networks.

Such a delay-sensitive system may dictate network technology. Direct transmission through the air by means of radio or infrared (optical wireless) would be faster than routing signals through fibres that take a more tortuous route, especially since the speed of light in fibre is only two third that in air.

Ultimately, there is a final solution if speed of computing increases so far that transmission delay is too big a problem. The processing engines could actually be shared, with all the deals and information processing taking place in a central computer, using massive parallelism. It would be possible to construct such a machine that treated each subscribing company fairly.

An interesting future side effect of all this is that the predicted flood of people into the countryside may be averted. Even though people can work from anywhere, their computers have to be geographically very close to the information centres, i.e. the City. Automated dealing has to live in the city, human based dealing can work from anywhere. If people and machines have to work together, perhaps they must both work in the City.

Consumer dealing

The stock exchange long since stopped being a trading floor with scraps of paper and became a distributed computer environment – it effectively moved into cyberspace. The deals still take place, but in cyberspace. There are no virtual environments yet, but the other tools such as automated buying and selling already exist. These computers are becoming smarter and exist in cyberspace every bit the same as the people. As a result, there is more automated analysis, more easy visualisation and more computer assisted dealing. People will be able to see which shares are doing well, spot trends and act on their computer’s advice at a button push. Markets will grow for tools to profit from shares, whether they be dealing software, advice services or visualisation software.

However, as we see more people buying personal access to share dealing and software to determine best buys, or even to automatically buy or sell on certain clues, we will see some very negative behaviours. Firstly, traffic will be highly correlated if personal computers can all act on the same information at the same time. We will see information waves, and also enormous swings in share prices. Most private individuals will suffer because of this, while institutions and individuals with better software will benefit. This is because prices will rise and fall simply because of the correlated activity of the automated software and not because of any real effects related to the shares themselves. Institutions may have to limit private share transactions to control this problem, but can also make a lot of money from modelling the private software and thus determining in advance what the recommendations and actions will be, capitalising enormously on the resultant share movements, and indeed even stimulating them. Of course, if this problem is generally perceived by the share dealing public, the AI software will not take off so the problem will not arise. What is more likely is that such software will sell in limited quantities, causing the effects to be significant, but not destroying the markets.

A money making scam is thus apparent. A company need only write a piece of reasonably good AI share portfolio management software for it to capture a fraction of the available market. The company writing it will of course understand how it works and what the effects of a piece of information will be (which they will receive at the same time), and thus able to predict the buying or selling activity of the subscribers. If they were then to produce another service which makes recommendations, they would have even more notice of an effect and able to directly influence prices. They would then be in the position of the top market forecasters who know their advice will be self fulfilling. This is neither insider dealing nor fraud, and of course once the software captures a significant share, the quality of its advice would be very high, decoupling share performance from the real world. Only the last people to react would lose out, paying the most, or selling at least, as the price is restored to ‘correct’ by the stock exchange, and of course even this is predictable to a point. The fastest will profit most.

The most significant factor in this is the proportion of share dealing influenced by that companies software. The problem is that software markets tend to be dominated by just two or three companies, and the nature of this type of software is that their is strong positive reinforcement for the company with the biggest influence, which could quickly lead to a virtual monopoly. Also, it really doesn’t matter whether the software is on the visualisation tools or AI side. Each can have a predictability associated with it.

It is interesting to contemplate the effects this widespread automated dealing would have of the stock market. Black Monday is unlikely to happen again as a result of computer activity within the City, but it certainly looks like prices will occasionally become decoupled from actual value, and price swings will become more significant. Of course, much money can be made on predicting the swings or getting access to the software-critical information before someone else, so we may see a need for equalised delivery services. Without equalised delivery, assuming a continuum of time, those closest to the dealing point will be able to buy or sell quicker, and since the swings could be extremely rapid, this would be very important. Dealers would have to have price information immediately, and of course the finite speed of light does not permit this. If dealing time is quantified, i.e. share prices are updated at fixed intervals, the duration of the interval becomes all important, strongly affect the nature of the market, i.e. whether everyone in that interval pays the same or the first to act gain.

Also of interest is the possibility of agents acting on behalf of many people to negotiate amongst themselves to increase the price of a company’s shares, and then sell on a pre-negotiated time or signal.

Such automated systems would also be potentially vulnerable to false information from people or agents hoping to capitalise on their correlated behaviour.

Legal problems are also likely. If I write, and sell to a company, a piece of AI based share dealing software which learns by itself how stock market fluctuations arise, and then commits a fraud such as insider dealing (I might not have explained the law, or the law may have changed since it was written), who would be liable?

And ultimately

Finally, the 60s sci-fi film, The Forbin Project, considered a world where two massively powerful computers were each assigned control of competing defence systems, each side hoping to gain the edge. After a brief period of cultural exchange, mutual education and negotiation between the machines, they both decided to co-operate rather than compete, and hold all mankind at nuclear gunpoint to prevent wars. In the City of the future, similar competition between massively intelligent supercomputers in share dealing may have equally interesting consequences. Will they all just agree a fixed price and see the market stagnate instantly, or could the system result in economic chaos with massive fluctuations. Perhaps we humans can’t predict how machines much smarter than us would behave. We may just have to wait and see.

End of original blog piece